Examples of inertia: 7 Real-Life Demonstrations You Can See Today

Examples of inertia explained through everyday situations and simple physics demos that illustrate Newton's First Law and practical takeaways for students.

Inertia is the unseen principle governing everything from your morning commute to a figure skater's elegant spin. It’s the real-world application of Newton's First Law of Motion: an object will maintain its state of rest or uniform motion unless an external force acts upon it. But what does that truly mean in practice? This comprehensive listicle moves beyond basic definitions to dissect 10 powerful examples of inertia, providing a clear and practical understanding of this fundamental concept.

Each example is structured for deep learning, not just surface-level recognition. We will explore the underlying physics of why you lurch forward when a car brakes suddenly, how astronauts navigate the zero-gravity environment of space, and the science behind the classic tablecloth-yanking trick. This article offers a strategic breakdown for each scenario, complete with actionable takeaways and thought experiments to solidify your knowledge.

You will gain a robust framework for identifying and analyzing inertia in various contexts, from everyday occurrences to classic classroom demonstrations. Whether you are a student tackling physics homework, a tutor seeking clear explanations, or simply a curious mind, this guide will equip you with the insights to master one of science's most essential laws.

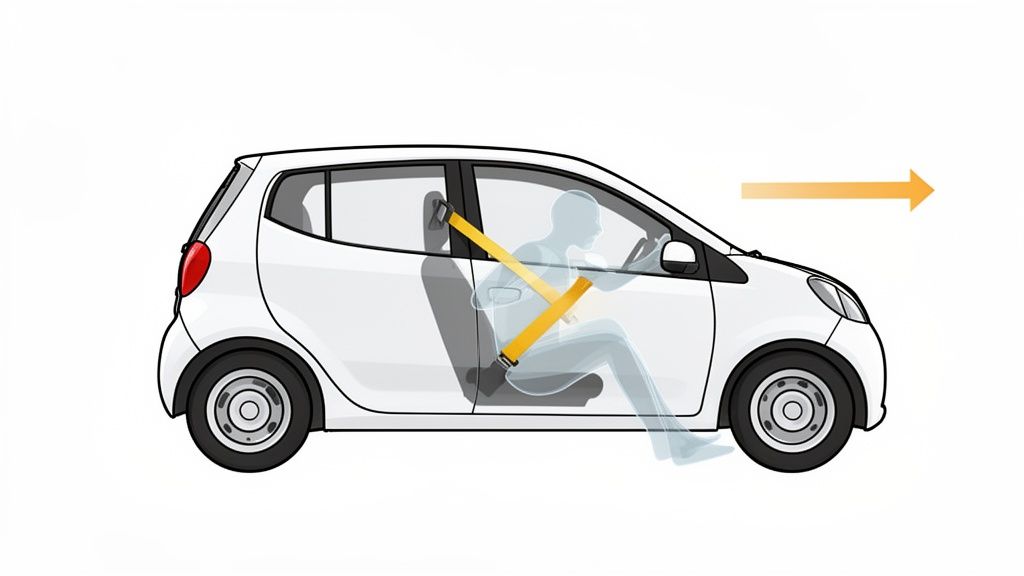

1. Vehicle Braking and Seatbelt Necessity

One of the most powerful and life-saving examples of inertia is experienced every time you are in a moving vehicle. According to Newton's First Law of Motion, an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force. When a car is moving, you and everything inside it are traveling at the same velocity as the car.

If the driver suddenly applies the brakes, an external force (friction from the brakes) acts on the car, causing it to decelerate. However, no such force is acting directly on your body. Your inertia, your resistance to a change in your state of motion, causes you to continue moving forward at the car's original speed. This is why seatbelts are crucial; they provide the necessary external force to safely slow you down with the vehicle, preventing you from hitting the dashboard or windshield.

Practical Application and Safety

Understanding this principle is fundamental to vehicle safety design. Crash test simulations, like the one shown below, vividly demonstrate how a passenger's inertia carries them forward during a collision.

Airbags work on the same principle, deploying rapidly to create a cushion that applies a stopping force to your body over a slightly longer period, reducing the potential for injury. The immense force required to overcome inertia is also why it's critical to understand the factors involved when you calculate stopping distance, as this directly relates to safe driving practices. This same concept of inertia also applies to motorcycle safety, where gear is designed to protect a rider who may be thrown from the vehicle.

2. Sliding Objects on Frictionless Surfaces

A classic demonstration of inertia can be observed by watching an object slide across a nearly frictionless surface, like a hockey puck on ice. According to Newton's First Law of Motion, an object in motion will remain in motion at a constant velocity unless acted upon by a net external force. The smooth ice minimizes the force of friction, allowing the puck to maintain its state of motion for a long time.

When a player strikes the puck, it is set in motion. After leaving the stick, the primary force acting on it horizontally is negligible friction. Its inertia, or its inherent resistance to changes in motion, keeps it sliding in a straight line at a nearly constant speed. It only changes its velocity when another force is applied, such as a collision with another player's stick, the boards, the net, or the eventual, gradual slowing from friction. This makes it one of the clearest real-world examples of inertia.

Practical Application and Demonstrations

This principle is not just visible in hockey or curling; it's a fundamental concept in physics education. Air hockey tables create a cushion of air to create a low-friction environment, perfectly demonstrating how an object maintains its velocity.

In a lab setting, experiments with sliding blocks or carts on low-friction tracks are used to verify Newton's laws. Understanding this inertial motion is a key step before analyzing more complex scenarios. While a sliding puck primarily demonstrates linear inertia, understanding forces is also foundational for concepts like what is projectile motion in physics, where gravity acts as the constant external force changing the object's vertical velocity.

3. Spinning Dancer or Figure Skater Momentum Conservation

A captivating example of inertia in rotational motion can be seen when a figure skater performs a spin. This principle is governed by rotational inertia, also known as the moment of inertia, which is an object's resistance to changes in its rotational motion. An object's moment of inertia depends not just on its mass, but also on how that mass is distributed relative to the axis of rotation.

When a skater begins a spin with their arms extended, their mass is distributed farther from their central axis, resulting in a large moment of inertia. As they pull their arms in close to their body, they decrease this distribution of mass. To conserve angular momentum (the rotational equivalent of linear momentum), their rotational speed must increase dramatically. This stunning acceleration happens without any external push or pull, perfectly illustrating how modifying rotational inertia changes an object’s state of motion.

Practical Application and Demonstrations

This principle of angular momentum conservation is not just for athletes; it's a fundamental concept in physics that applies to everything from planetary orbits to the tumbling maneuvers of gymnasts and divers. The video below shows a simple classroom demonstration that makes this complex idea easy to grasp.

By holding weights and spinning on a rotating chair, the demonstrator can change their rotational speed just by extending or retracting their arms. This provides a tangible feel for how redistributing mass alters rotational inertia. This is one of the most effective examples of inertia because it visibly connects an action (moving arms) to an immediate and dramatic reaction (changing spin speed), reinforcing the core concepts of rotational dynamics.

4. Tablecloth Yanking Magic Trick

A classic and visually stunning demonstration of inertia is the tablecloth trick. In this famous "magic" act, a tablecloth is swiftly pulled from underneath a full set of dishes, leaving the dinnerware almost undisturbed on the table. This works because of Newton's First Law: the dishes, at rest, possess inertia and will resist a change in their state of motion.

When the tablecloth is yanked with enough speed and force, the brief frictional force acting on the dishes is not applied for long enough to overcome their inertia. The dishes resist the motion and stay in place, seemingly by magic. This makes it one of the most memorable examples of inertia, commonly seen in physics classrooms, science fairs, and even viral social media challenges where people test Newton's laws in a dramatic fashion.

Practical Application and Demonstrations

The key to successfully performing this trick lies in minimizing the time the frictional force acts on the objects. A quick, sharp, downward pull is essential. The video below breaks down the physics behind this amazing demonstration.

This principle isn't just for show; it applies to any situation where a sudden, brief force is exerted on an object with significant inertia. For instance, quickly snapping a piece of paper from under a coin without moving the coin works the same way. The tablecloth trick is a powerful tool for educators to make the abstract concept of inertia tangible and exciting for students.

5. Astronaut Movement in Zero Gravity

A common misconception is that in the "weightlessness" of space, objects have no inertia. In reality, the microgravity environment of an orbiting spacecraft provides a perfect stage to observe one of the purest examples of inertia, demonstrating that an object’s resistance to changes in motion is entirely separate from the force of gravity. Mass, and therefore inertia, remains constant regardless of location.

On the International Space Station (ISS), an astronaut at rest will remain at rest, floating in place, until they apply a force. To move, they must push off a wall or another object. Once in motion, their inertia causes them to continue moving in a straight line at a constant velocity until they collide with another surface, which provides the external force needed to stop them. This is a direct, observable demonstration of Newton's First Law.

Practical Application and Space Operations

Understanding this principle is critical for all space operations, from mission planning to spacecraft design. Astronauts must carefully manage their movements to avoid uncontrolled collisions that could damage sensitive equipment or cause injury. Even a small, slowly moving tool has inertia and can cause damage if it drifts into a critical system.

This video from the ISS clearly shows how astronauts utilize and account for inertia. Notice how they use slight pushes for navigation and must grab onto handrails to arrest their motion. This same principle dictates how satellites are maneuvered in orbit; small thruster burns provide the necessary force to overcome the spacecraft's inertia and alter its trajectory.

6. Car Skidding on Wet or Icy Roads

Another critical, real-world example of inertia occurs when a vehicle attempts to stop on a low-friction surface like ice or a wet road. Newton's First Law states that an object in motion will remain in motion unless an external force acts upon it. When a car is moving, its mass and velocity give it significant forward inertia.

If the driver slams on the brakes, the wheels may lock up. On a dry road, the friction between the tires and the pavement is strong enough to overcome the car's inertia and bring it to a stop. On ice, however, this friction is drastically reduced. The car's powerful inertia keeps it moving forward, causing it to skid uncontrollably. The external stopping force is insufficient to change the vehicle's state of motion, vividly demonstrating how inertia can overpower braking attempts.

Practical Application and Safety

This principle is the reason behind the invention of anti-lock braking systems (ABS). ABS prevents the wheels from locking up during a hard brake, allowing the tires to maintain some rotational traction with the road surface. This "pulsing" action helps the force of friction overcome the car's inertia more effectively.

Understanding this concept is vital for safe winter driving. Highway safety administrations often publish data showing increased accident rates in icy conditions, directly linked to drivers underestimating their vehicle's inertia and the increased stopping distance required. The difference in kinetic energy between a car at 30 mph versus 60 mph highlights why even a small increase in speed can make overcoming inertia on ice nearly impossible, leading to dangerous skids.

7. Pendulum Motion and Swinging

A swinging pendulum offers a classic and elegant demonstration of inertia in oscillating motion. Newton's First Law states that an object in motion will stay in motion. When a pendulum's bob is pulled back and released, gravity pulls it down toward its lowest point, or equilibrium. As it passes this point, its velocity is at a maximum.

The bob’s inertia, its tendency to resist changes in its state of motion, causes it to continue moving past the equilibrium point. It swings upwards against the force of gravity on the other side. Gravity eventually overcomes its momentum, bringing it to a momentary stop before pulling it back down. This cycle of gravity and inertia working in tandem creates the pendulum's rhythmic, predictable swing, a core principle behind timekeeping devices like grandfather clocks.

Practical Application and Demonstrations

The principle of the pendulum is not just for clocks; it's a fundamental concept in physics and engineering. From the simple swing on a playground to the massive seismic dampers used to stabilize skyscrapers during earthquakes, the predictable motion driven by inertia and gravity is key.

You can easily explore these examples of inertia yourself:

- Playground Swing: Notice how you continue moving forward past the lowest point of the arc. That's your inertia in action. To go higher, you must pump your legs, adding energy to overcome friction and air resistance that would otherwise cause the swinging to stop.

- Metronome: A weighted, inverted pendulum used by musicians relies on the same principles to keep a steady tempo. Adjusting the weight changes the period of the swing, altering the beat.

8. Passenger Luggage Movement During Airplane Turbulence

The experience of sudden turbulence on an airplane provides a compelling, large-scale demonstration of inertia. Newton's First Law of Motion states that an object in motion will remain in motion unless acted upon by an external force. While cruising, you, your luggage, and everything within the aircraft are moving at a constant velocity, typically hundreds of miles per hour, along with the plane itself.

When the plane hits a pocket of rough air and suddenly drops, accelerates, or changes direction, the aircraft's structure is immediately subjected to this new force. However, the passengers and any unsecured objects inside are not. Your body's inertia, its tendency to resist this change, causes you to continue along the original path of motion. If the plane drops suddenly, you feel a sensation of being lifted from your seat as your body tries to continue its forward and level trajectory.

Practical Application and Safety

This principle is why aviation safety regulations are so strict. The "fasten seatbelt" sign is illuminated during turbulence to provide the external force needed to keep you safely secured in your seat, moving with the plane instead of independently from it.

Overhead bins are designed with strong latches precisely to counteract the inertia of luggage, which could otherwise become dangerous projectiles during severe turbulence. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) guidelines and airline crew training emphasize securing the cabin because they understand that inertia doesn't just apply to people. A loose laptop or a heavy carry-on bag will continue its motion until stopped by a person or part of the cabin, highlighting why following crew instructions is essential for safety.

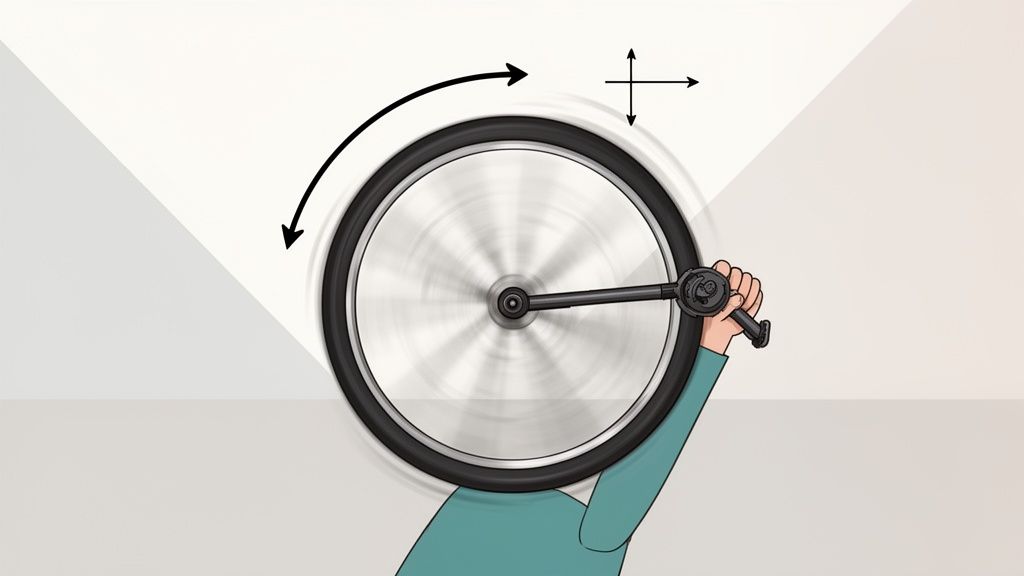

9. Rotating Bicycle Wheel Gyroscopic Effect

While many examples of inertia focus on linear motion (objects moving in a straight line), rotational inertia is equally fundamental and visually captivating. Newton's First Law also applies to rotating objects: a spinning object will keep spinning at the same rate and about the same axis unless acted upon by an external torque. This resistance to change in angular motion is powerfully demonstrated by a spinning bicycle wheel.

When you hold a spinning bicycle wheel by its axle and try to tilt it, you feel a strong, counterintuitive resistance. Instead of tilting easily, the wheel "precesses," meaning it tries to rotate around an axis perpendicular to your applied force. This gyroscopic effect is a direct consequence of the wheel’s angular momentum. The spinning mass possesses significant rotational inertia, making it resist any change to its axis of rotation.

Practical Application and Demonstrations

This principle isn't just a neat party trick; it's essential to how many technologies function. The stability of a moving bicycle, the operation of a simple spinning top, and the sophisticated attitude control systems in spacecraft and airplanes all rely on gyroscopic inertia to maintain orientation.

- Bicycle Stability: The rotational inertia of the spinning wheels helps keep a bicycle upright and stable while it's in motion.

- Spacecraft Navigation: Satellites and probes use gyroscopes to maintain their orientation in space without reference to Earth.

- Spinning Tops: A top can balance on a fine point only when spinning, as its rotational inertia resists the torque from gravity that would otherwise make it fall.

This gyroscopic effect is one of the most hands-on and memorable examples of inertia, illustrating how the principles of motion apply to spinning objects just as they do to objects moving in a straight line.

10. Bullet Penetration and Impact Physics

A high-velocity projectile, like a bullet, provides a dramatic example of inertia in action. According to Newton's First Law, once fired, the bullet will continue moving in a straight line at a constant speed due to its inertia. It will only stop or change direction when acted upon by an unbalanced force, such as air resistance or, more significantly, the impact with a target material.

When the bullet strikes a target, its high inertia (a product of its mass and velocity) means it resists slowing down. The target material must exert a massive stopping force to overcome this inertia. This force causes the bullet to penetrate the material, transferring its kinetic energy and deforming both itself and the target. The depth of penetration depends on the bullet's inertia and the resistive forces of the material.

Practical Application and Impact Analysis

This principle is fundamental in forensic science and materials engineering. Ballistic gelatin tests, like the one shown below, are used to simulate the effect of a projectile on soft tissue, clearly demonstrating how inertia carries the bullet through the medium.

Engineers apply these concepts to design effective body armor and protective barriers for vehicles and aerospace applications. By understanding the forces required to overcome a projectile's inertia, they can develop materials that dissipate energy and provide sufficient resistance. The relationship between force, mass, and acceleration is key here; you can learn more about how these concepts connect by reading about Newton's second law. This makes impact physics a critical field for safety and defense technology.

Comparison of 10 Inertia Examples

| Example | Implementation complexity | Resource requirements | Expected outcomes | Ideal use cases | Key advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Braking and Seatbelt Necessity | Medium — needs controlled demos or videos | Moderate — crash-test data, safety gear, video resources | Understand linear inertia, force vectors, and importance of restraints | Driver safety education, mechanics courses, applied demos | Strong real-world relevance; directly ties physics to safety |

| Sliding Objects on Frictionless Surfaces | Low — simple setups or videos | Low — puck/air table, smooth surfaces, slow‑mo video | Observe near-ideal inertial motion and friction effects; simple calculations | Lab experiments, intro mechanics, sports examples | Clear, easy-to-calculate demonstration of Newton’s First Law |

| Spinning Dancer / Figure Skater Momentum Conservation | Medium — requires rotational explanation | Low — videos, rotating chair, small masses | Conservation of angular momentum and moment of inertia concepts | Advanced high-school/AP lessons, outreach demos, college mechanics | Visually striking; links rotational theory to familiar activities |

| Tablecloth Yanking Magic Trick | Low — simple but technique-dependent | Low — cloth, dishes, smooth table; safety precautions | Illustrates inertia vs. friction and importance of rapid force application | Classroom demonstrations, outreach, informal experiments | Highly engaging and memorable; easy to grasp intuitively |

| Astronaut Movement in Zero Gravity | High — non-terrestrial environment | High — ISS/parabolic flight footage or simulations | Shows inertia independent of gravity and motion in isolated systems | Aerospace education, advanced mechanics, motivational lessons | Demonstrates extreme conditions; strong conceptual clarity about reference frames |

| Car Skidding on Wet or Icy Roads | Medium — many real-world variables | Moderate to high — simulations, data, controlled testing | Understand reduced friction, increased stopping distance, ABS operation | Driver safety training, vehicle engineering, applied labs | Direct safety application; motivates study of friction and vehicle systems |

| Pendulum Motion and Swinging | Low — classic, repeatable experiment | Low — string, bob, stopwatch; simple apparatus | Demonstrates SHM, period dependence on length, energy exchange | Intro physics labs, timing experiments, demonstrations on waves | Historically significant, easy construction, rich for quantitative analysis |

| Passenger Luggage Movement During Airplane Turbulence | Medium — involves non-inertial frames | Moderate — flight videos, simulations, flight data | Illustrates apparent forces, reference frames, and cabin safety measures | Aviation safety education, mechanics courses emphasizing frames | Relatable everyday example; introduces non-inertial reference concepts |

| Rotating Bicycle Wheel Gyroscopic Effect | Medium — needs rotational setup | Low — spinning wheel, axle, hands-on demo | Demonstrates precession, angular momentum vectors, torque response | Interactive demos, engineering examples, rotational mechanics labs | Hands-on and dramatic; connects theory to tangible experience |

| Bullet Penetration and Impact Physics | High — safety and sensitivity concerns | High — ballistic tests, specialized data or vetted videos | Shows momentum, kinetic energy dissipation, material resistance | Forensics, materials science, advanced physics (with caution) | Strong application to real-world engineering and forensic analysis |

From Theory to Reality: Making Inertia Work for You

Throughout this comprehensive exploration, we have journeyed from the familiar jolt of a braking car to the weightless drift of an astronaut in space. The ten examples of inertia we've dissected do more than just illustrate a physics concept; they reveal a fundamental principle that actively shapes our reality every moment of every day. We’ve seen how this resistance to change in motion is not an abstract idea, but a tangible, predictable, and even harnessable force.

The core insight connecting all these examples, from the dramatic tablecloth yank to the graceful pirouette of a figure skater, is that mass is the ultimate measure of inertia. An object's reluctance to start moving, stop moving, or change direction is directly proportional to how much "stuff" it's made of. This isn't just a fact to memorize; it's a strategic key. It explains why a massive cargo ship takes miles to stop and why a tiny bullet can have such a devastating impact.

Key Takeaways: From Observation to Application

Mastering the concept of inertia moves you from a passive observer of the world to an active participant who understands its mechanics. Here are the most crucial takeaways to carry forward:

Inertia is a Property, Not a Force: One of the most common misconceptions is thinking of inertia as an active force pushing or pulling on an object. Remember, inertia is a property of mass that describes an object's inherent resistance to having its state of motion changed by an external force. This distinction is critical for correctly applying Newton's Laws.

Mass is the Measure: Whether you are analyzing linear or rotational inertia, the distribution and amount of mass are the defining factors. A spinning dancer pulling their arms in isn't changing their mass, but they are changing its distribution, which directly impacts their rotational inertia and, consequently, their speed.

Safety is Applied Physics: Concepts like seatbelts and car crumple zones are not arbitrary additions. They are brilliant engineering solutions designed specifically to manage the consequences of inertia. By understanding the physics, you can better appreciate the life-saving technology around you and make safer decisions.

Your Next Steps: Putting Inertia into Practice

Understanding these principles is the first step; applying them is how true mastery is achieved. The next time you are in a moving vehicle, consciously think about how your body continues to move forward when the car slows down. When you see a sport being played, look for how athletes manipulate their inertia to gain an advantage.

This principle is a cornerstone of classical mechanics. By truly grasping the diverse examples of inertia, you build a solid foundation for tackling more complex topics like momentum, energy, and forces. It empowers you to analyze problems, design solutions, and see the intricate, predictable physics woven into the fabric of the world. Keep observing, keep questioning, and you will see these laws in action everywhere.

Feeling stuck on a homework problem or need a personalized explanation for how inertia applies to a specific scenario? Get instant, step-by-step guidance with Feen AI. Our AI tutor can analyze diagrams, break down complex concepts, and help you connect the theory you've learned here to your specific assignments. Visit Feen AI to turn confusion into clarity.

Relevant articles

Explore change in momentum, including impulse and the core formula, with clear explanations and practical examples to sharpen problem solving.

Discover what is projectile motion in physics, with clear explanations, real-world examples, and quick formulas to master the basics.