What Is Newton's Second Law A Guide to F=ma

Struggling with 'what is Newton's second law'? This guide explains the F=ma formula with clear analogies, real-world examples, and step-by-step problem-solving.

Newton's Second Law of Motion essentially tells us that an object's acceleration is tied directly to two things: the total force pushing or pulling on it and its mass. Put simply, the harder you push something, the more it accelerates. But at the same time, the heavier it is, the more force you'll need to get it moving at that same rate.

This fundamental relationship is what we know and love as the equation F = ma.

Defining the Law of Acceleration

At its core, the second law gives us a solid mathematical bridge connecting the concepts of force, mass, and acceleration. It's not just a vague description; it's a predictive tool. It lets us calculate exactly how an object's motion will change when a force is applied.

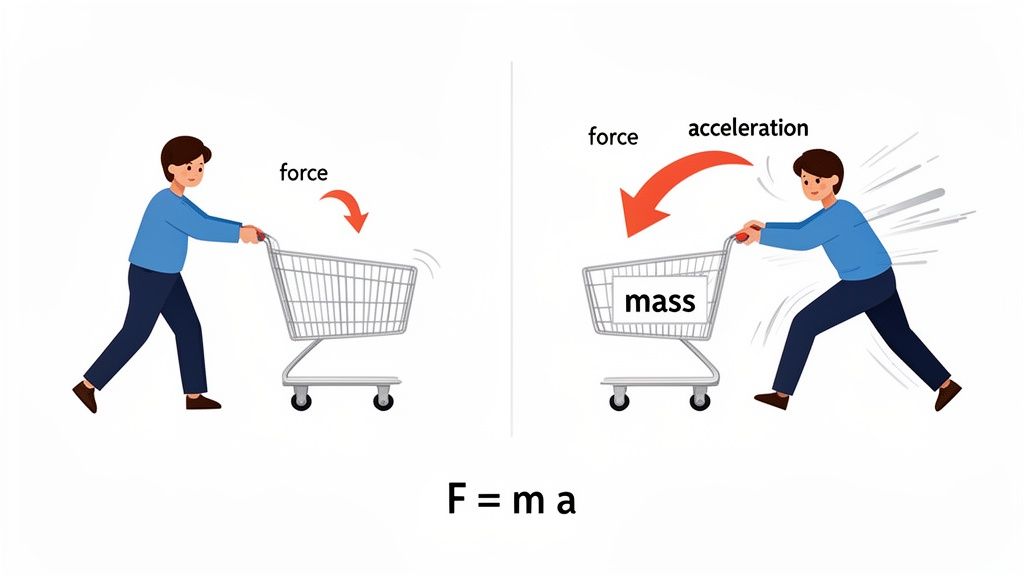

Think about it in the grocery store. A light tap on an empty shopping cart gets it rolling, but you need a much bigger shove to get a full one moving with the same urgency. That’s the second law in action.

This groundbreaking idea was formally introduced by Sir Isaac Newton on July 5, 1687, in his masterpiece, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. This was a huge departure from the old Aristotelian view that a constant force was needed just to keep something moving. Newton flipped that on its head, showing that force isn’t required to sustain motion, but to change it—in other words, to cause acceleration. For a deeper dive into the history, you can find more great insights on Vparchery.com.

The Two Essential Formulas

While most of us learn the simple version first, Newton's Second Law actually comes in two flavors. Each one gives us a slightly different lens for looking at how forces affect an object.

- F = ma: This is the one everyone knows. It perfectly describes the relationship between net force (F), mass (m), and acceleration (a). It’s your go-to formula for any problem where the object's mass stays the same.

- F = dp/dt: This is the more complete and original formulation. It states that the net force (F) is equal to the rate of change of momentum (p) over time (t). This version is absolutely essential when you're dealing with systems where mass isn't constant, like a rocket expelling fuel.

Key Takeaway: Force doesn't cause motion; it causes acceleration (a change in motion). An object cruising along at a constant velocity has zero net force acting on it.

To really get a handle on this, it helps to break down the classic F = ma formula into its parts.

Key Components of Newton's Second Law (F = ma)

The table below lays out each piece of the equation, what it means, and how we measure it.

| Variable | Symbol | Definition | Standard Unit (SI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Force | F | The total push or pull on an object after all individual forces are added up. | Newton (N) |

| Mass | m | A measure of an object's inertia—its natural resistance to a change in motion. | Kilogram (kg) |

| Acceleration | a | The rate at which an object's velocity changes over a period of time. | Meters per second squared (m/s²) |

Understanding these three components is the first step to mastering the law and using it to solve real-world physics problems.

Unpacking the Core Formula: F = ma

At first glance, the equation F = ma looks simple enough. But those three letters pack a punch, describing everything from how a soccer ball flies through the air to how planets stay in orbit. To really get a feel for what Newton's second law is, we need to go beyond the letters and understand the physical story they tell.

It all starts with the idea of net force. In the real world, objects are rarely pushed or pulled by just one force. Think about a game of tug-of-war. You have two teams pulling on a rope in opposite directions. If they pull with the exact same strength, nothing happens—the rope stays put. The net force is zero.

But what happens the second one team gives a mightier tug? The forces are no longer balanced. The rope, and everyone holding it, starts accelerating in the direction of that stronger pull. That combined, overall force is the "F" in our equation. It’s the sum of all the forces at play.

The Key Players: Force, Mass, and Acceleration

Let's break down each part of the formula. It helps to think of them as characters in a drama, each with a specific role.

- Force (F): This is the main action—the "push" or "pull" that gets things moving. Importantly, force is a vector. It doesn't just have a size (how strong is the push?); it also has a direction (which way is it pushing?).

- Mass (m): This is the object’s stubbornness, its built-in resistance to being moved. Scientists call this inertia. A bowling ball has a lot more mass than a tennis ball, so you instinctively know it’s going to be much harder to get it rolling.

- Acceleration (a): This is the outcome of the action. It's the change in an object's velocity—either its speed, its direction, or both—that happens because a net force was applied.

Picture yourself pushing a shopping cart. The effort from your arms is the force. The cart and its contents represent the mass. And the way the cart picks up speed is its acceleration. These three aren't just related; they're completely intertwined.

Crucial Insight: An object with zero net force on it isn't always sitting still. It could be moving at a perfectly constant velocity. Think of a car on cruise control on a straight, flat highway. The engine's push forward is perfectly canceled out by air resistance and friction, so the net force is zero, and the car's speed doesn't change.

Understanding the Proportional Relationships

The real elegance of F = ma is in how the variables relate to each other. It’s all about simple, predictable proportions.

Force and Acceleration are Directly Proportional

If you keep the mass the same, whatever you do to the force, you do to the acceleration. Double the force, and you double the acceleration.

- Example: Imagine pushing a shopping cart with a gentle, steady push. It accelerates at a certain rate. Now, push that same cart with twice the force. You'll see it accelerate at twice the rate, as long as you haven't added any groceries.

Mass and Acceleration are Inversely Proportional

If you keep the force the same, mass and acceleration have the opposite effect on each other. Double the mass, and you cut the acceleration in half.

- Example: Give an empty shopping cart a steady push. Now, load it up with heavy items, doubling its mass. If you push with that exact same force as before, the full cart will only accelerate at half the rate of the empty one.

To dig deeper, it's useful to explore the basic formula for force calculation and its applications. Once these simple relationships click, you're well on your way to solving physics problems. And if you want a quick reference for this and other core equations, our https://feen.ai/blog/physics-formulas-cheat-sheet is a great tool to keep handy.

This intuitive connection—between pushing something, the "stuff" it's made of, and how its motion changes—is the heart and soul of Newton's Second Law.

Solving Problems with Free-Body Diagrams

Knowing the formula F = ma is one thing, but actually using it to solve physics problems is where the rubber meets the road. This is where theory gets practical and you start building the skills to ace your exams. And the single most crucial tool in your arsenal for applying Newton's Second Law is the free-body diagram.

Think of it as your strategic map for any physics problem. It’s a simple sketch that helps you isolate an object and visualize every single force acting on it. Drawing one out turns a messy, confusing scenario into a set of clean algebra equations, ensuring you don't miss a thing.

This diagram neatly shows the relationship: a net force acting on a mass is what causes it to accelerate. Your job is to find all the forces.

A Four-Step Method for Nailing Any Problem

To consistently get the right answer, you need a process you can rely on every time. Follow these four steps to break down any problem involving forces and motion.

- Identify All Forces: Before you draw anything, just list every force you can think of acting on the object. Is there gravity (weight)? A push from a surface (normal force)? A pull from a rope (tension)? Friction? Get them all down.

- Draw the Free-Body Diagram: This is the visual step. Represent your object as a simple dot or a box. Then, from that central point, draw an arrow for each force on your list. Make sure each arrow points in the right direction and has a clear label (like W for weight or T for tension).

- Choose a Coordinate System: Slap an x-y axis right onto your diagram. Making a smart choice here can save you a ton of mathematical headaches later. For a box on a ramp, for instance, tilting your axes to line up with the slope is almost always the best move.

- Apply Newton's Second Law (Separately!): This is the final step. Write out the ΣF = ma equation for each axis. Add up all the forces in the x-direction and set them equal to

maₓ. Then do the same thing for the y-direction (maᵧ). Now you have a system of equations you can solve.

Pro Tip: If an object isn't accelerating in a particular direction—like a box on a table not flying into the air—the net force in that direction is zero. This is just a special case of the second law where

a = 0, and it really simplifies your calculations.

Worked Example: A Block on a Flat Table

Let's try this out. We have a 10 kg box on a frictionless table. You pull it to the right with a rope, applying a steady 20 N force. What’s the box’s acceleration?

Step 1: Identify Forces

- Weight (W): Gravity pulls the box down.

- Normal Force (N): The table pushes up, supporting the box.

- Tension (T): The rope pulls to the right with 20 N.

Step 2: Draw the Diagram

Imagine a box with an arrow pointing down (W), an arrow up (N), and an arrow to the right (T).

Step 3: Set Up Coordinates

A standard x-y axis is perfect here. Let's make the positive x-axis point right and the positive y-axis point up.

Step 4: Apply F = ma

- Y-Direction: The box isn't moving up or down, so

aᵧ = 0. Our equation isΣFᵧ = N - W = maᵧ = 0. This tells us thatN = W, meaning the normal force and weight cancel out completely. They're important, but they don't affect the horizontal motion. - X-Direction: The only horizontal force is the tension from the rope. So,

ΣFₓ = T = maₓ.

Solution:

We just need to solve the x-direction equation: T = maₓ.

Plugging in what we know: 20 N = (10 kg) * aₓ.

Solving for aₓ is simple: aₓ = 20 N / 10 kg = 2 m/s².

The box accelerates to the right at 2 m/s². See? The process works.

Worked Example: A Block on an Inclined Ramp

Ready for a classic? A 5 kg block is on a frictionless ramp tilted at a 30-degree angle. It starts sliding down. How fast does it accelerate?

Step 1: Identify Forces

- Weight (W): Gravity always pulls straight down, toward the Earth's center.

- Normal Force (N): The ramp pushes back on the block, perpendicular to its surface.

Step 2: Draw the Diagram

Sketch the block on the slope. The normal force (N) points away from the ramp's surface at a 90-degree angle. The weight (W) points straight down.

Step 3: Set Up Coordinates

Here’s the trick! Tilt your coordinate system. Make the x-axis point down the ramp (the direction of motion) and the y-axis perpendicular to it. This makes the math so much easier. Now, the Normal Force is entirely in the y-direction, but Weight is at an angle and must be split into components: one parallel to the ramp (Wₓ) and one perpendicular to it (Wᵧ).

Step 4: Apply F = ma

Using some basic trigonometry, the part of gravity pulling the block down the ramp is Wₓ = W * sin(30°).

- Y-Direction: The block isn't jumping off or crashing through the ramp, so

aᵧ = 0. The equation isΣFᵧ = N - Wᵧ = 0. - X-Direction: The only force driving the motion down the ramp is the parallel component of gravity. Our equation is

ΣFₓ = Wₓ = maₓ.

Solution:

First, let's find the block's weight: W = mg = 5 kg * 9.8 m/s² = 49 N.

Next, calculate the component of weight pulling it down the ramp: Wₓ = 49 N * sin(30°) = 24.5 N.

Now, we can use our x-direction equation: 24.5 N = (5 kg) * aₓ.

Solving for the acceleration: aₓ = 24.5 N / 5 kg = 4.9 m/s².

The block accelerates down the ramp at 4.9 m/s². Learning how to break forces into components is a fundamental skill, especially when you get into two-dimensional problems, which you can read about in our guide to what is projectile motion in physics.

Going Deeper With The Momentum Formula

While F = ma is the version of Newton's second law everyone remembers from school, it's actually a special case of a more fundamental and powerful principle. The original, more complete law states that force is equal to the rate of change of an object's momentum.

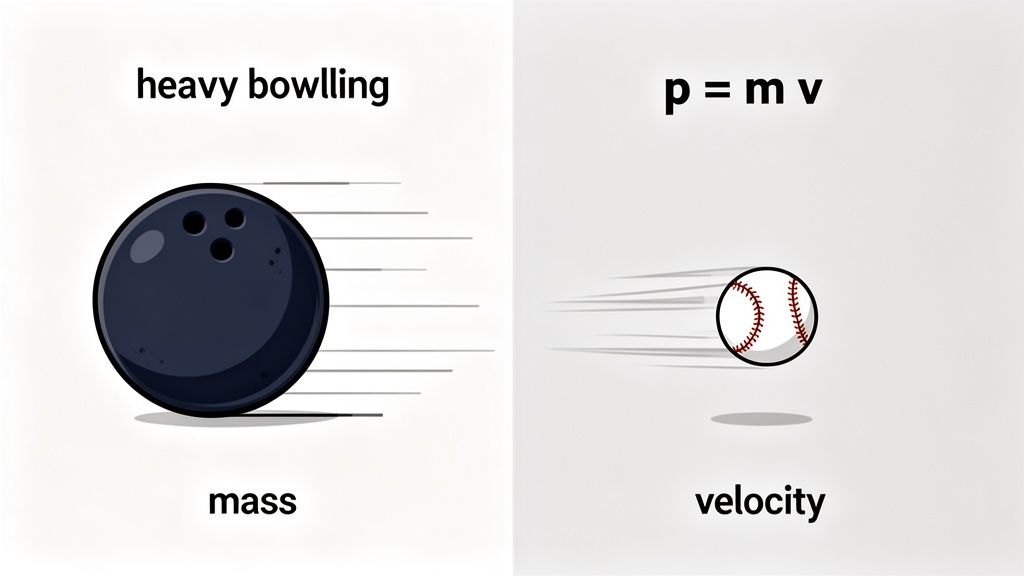

This deeper law is written as F = dp/dt. Let's break that down. The "p" stands for momentum, which you can think of as "mass in motion." It's calculated by multiplying mass by velocity (p = mv). The "d/dt" part is from calculus, and it just means "the rate of change with respect to time."

So, this formula is telling us that applying a net force to something changes its momentum over time.

What Is Momentum, Anyway?

Momentum is a core concept in physics that captures both how much stuff is in an object (its mass) and how fast that stuff is moving (its velocity). It's a single value that packs a lot of information.

For instance, a heavy bowling ball rolling slowly can have the exact same momentum as a lightweight baseball thrown at incredible speed. The bowling ball has a huge mass but a tiny velocity, while the baseball has a tiny mass but a huge velocity. The product of mass times velocity could be identical for both.

Key Insight: Thinking about force as a change in momentum is a more fundamental way to understand what Newton's second law is. It holds true in more situations than F = ma alone.

Deriving F = ma From The Momentum Formula

If F = dp/dt is the real deal, where did the famous F = ma come from? It's derived directly from the momentum equation, but it relies on one very important assumption: the object's mass is constant.

Let’s walk through the logic:

- Start with the full law:

F = dp/dt - Substitute the definition of momentum (p): We know

p = mv, so the equation becomesF = d(mv)/dt. - Apply the product rule: For those familiar with a bit of calculus, we apply the product rule for derivatives, which gives us

F = m(dv/dt) + v(dm/dt). - Make the key assumption: In most everyday scenarios—pushing a box, kicking a ball—the object's mass doesn't change. This means the rate of change of mass (

dm/dt) is zero, and that whole second term just vanishes. - Simplify the result: We're left with

F = m(dv/dt). And since the rate of change of velocity (dv/dt) is just the definition of acceleration (a), we arrive at our familiar friend: F = ma.

This shows that F = ma is simply a convenient shortcut for constant-mass systems. Historically, this law, published in 1687, was foundational. It allowed for the derivation of other key principles like the Impulse-Momentum theorem, showcasing its incredible power in classical mechanics.

Comparing F = ma and F = dp/dt

To make the distinction crystal clear, it helps to see the two forms of the law side-by-side. Each has its place, but one is undeniably more universal than the other.

| Aspect | F = ma (Constant Mass) | F = dp/dt (General Form) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | Force is mass times acceleration. | Force is the rate of change of momentum. |

| Assumption | Mass of the object is constant. | No assumption needed; mass can vary. |

| Best Use Case | Everyday mechanics: cars, falling objects, pushing furniture. | Systems with changing mass: rockets, conveyor belts. |

| Scope | A specific case of the more general law. | The fundamental, universal form of the law. |

Ultimately, while F = ma gets the job done for most high school physics problems, F = dp/dt is the version that works everywhere, from launching spaceships to analyzing subatomic particles.

When Mass Changes, The Real World Gets Interesting

The full momentum formula F = dp/dt isn't just an academic exercise; it's essential for systems where mass isn't constant. The classic example is a rocket blasting off into space.

As a rocket burns fuel, it continuously ejects massive amounts of hot gas from its engines. This means the rocket's total mass is constantly decreasing. If engineers tried to use F = ma to calculate its acceleration, their numbers would be wrong because 'm' isn't a fixed value. They must use the general form, F = dp/dt, to get it right.

For those looking to dive into these more advanced topics or read original research, learning how to read scientific papers efficiently is a vital skill. Understanding this deeper, more complete version of Newton's second law opens the door to some of the most fascinating corners of physics.

Seeing Newton's Second Law All Around You

Physics often feels like something trapped in a textbook, a bunch of abstract equations with no connection to the real world. But Newton's Second Law is different. It's the invisible script that governs motion all around us, every single day.

Once you know what to look for, you'll see the relationship between force, mass, and acceleration everywhere. It's the reason you have to push a full shopping cart harder than an empty one. It’s why a tiny pebble is easy to throw, but a heavy boulder isn't.

Let's look at a few powerful, real-world examples that bring this fundamental law to life.

The Physics of Automotive Safety

Car safety engineering is one of the most important and life-saving applications of Newton’s Second Law. During a crash, a car experiences a massive and sudden deceleration. The goal of safety features like airbags and crumple zones isn't to prevent the change in momentum—that's impossible—but to stretch out the time it takes for that change to happen.

This all comes down to the impulse-momentum theorem, a direct consequence of F = ma. It tells us that Force × time = change in momentum (FΔt = Δp). In a collision, the change in your momentum (Δp) is fixed as you go from moving to a dead stop. By increasing the time of impact (Δt) with an airbag, the force (F) on your body is drastically reduced. A 0.1-second impact is far more survivable than a 0.01-second one.

This is a cornerstone of modern engineering. In fact, Newton's second law is applied in over 90% of structural designs globally, helping engineers make sure everything from bridges to buildings can handle the forces they'll face. In automotive safety, its impact is even more direct. According to 2023 NHTSA data, seatbelts—which also work by applying force over a longer duration—reduce crash-related fatalities by 45-50%.

To put numbers on it, a 70 kg person stopping from 15 m/s in 0.1 seconds experiences a survivable 10,500 N of force. That's a huge contrast to the deadly 105,000 N they would face in an instantaneous, unrestrained stop. For more fun examples, you can find a good breakdown of Newton's laws in real life on Geniebook.com.

Crucial Takeaway: Safety features don't reduce the total change in motion during a crash. They cleverly manipulate

F = maby increasing the stopping time to dramatically decrease the force on passengers.

The Science of Sports

Every sport is a live-action physics lab. Athletes are constantly manipulating force, mass, and acceleration, even if they don't think about it in those terms. When a soccer player kicks a ball, they apply a huge force for a split second to accelerate the ball from rest to a high speed. The more force they apply, the faster the ball goes.

Think about the difference between a gentle pass and a powerful shot on goal.

- The Pass: A small, controlled force creates a small acceleration and a low final speed.

- The Shot: A massive force generates huge acceleration, sending the ball rocketing toward the net.

The same principle is at work when a baseball player hits a home run or a golfer drives a tee shot. They aren't just swinging hard; they are trying to apply the maximum possible force to a small mass to get the greatest possible acceleration. This is a perfect demonstration of what Newton's second law is in a dynamic, competitive setting. You can see similar ideas at work when learning about the mechanical advantage of levers, which is another way of multiplying force.

Engineering Marvels Large and Small

From elevators to rockets, engineers lean heavily on Newton's Second Law. When designing an elevator, they have to calculate the tension needed in the cable to not only support the elevator's weight (mass × gravity) but also to provide the extra net force required to accelerate it upwards.

Rockets present an even more interesting problem. As a rocket burns fuel, its mass is constantly decreasing. This is a variable-mass system where the simple F = ma isn't enough. Engineers have to use the more general form of the law, F = dp/dt, to accurately model the rocket's increasing acceleration as it gets lighter—a perfect, real-world example of the deeper physics at work.

Avoiding Common Physics Pitfalls

When you're getting to grips with forces and motion, it's easy to stumble over a few common hurdles. Even concepts that seem straightforward, like what Newton's second law is, have subtle traps that can trip up the best of us. Let's walk through some of the most frequent sticking points so you can build real confidence for your homework and exams.

Mass vs. Weight: More Than Just Semantics

One of the biggest mix-ups, and a classic "gotcha" question, is confusing mass with weight. In everyday conversation, we use them interchangeably, but in physics, they're worlds apart. Mass is the amount of "stuff" an object is made of—it’s a measure of its inertia. Weight, however, is the force of gravity pulling down on that mass.

Crucial Distinction: Think of an astronaut. Their mass—the amount of matter in their body—is the same whether they're on Earth or floating on the Moon. But their weight? On the Moon, it’s only about 1/6th of what it is on Earth, all because the Moon's gravity is so much weaker.

The "Constant Push" Fallacy

Another old idea that’s tough to shake comes from Aristotle, who thought you needed a constant force to keep something moving at a constant speed. Newton turned this on its head. A force isn't needed to maintain motion, it's needed to change it—in other words, to accelerate it.

Picture a hockey puck sliding across a frictionless sheet of ice. After the initial push, it just glides along at a steady velocity. No one is continuously pushing it. That initial shove got it moving (it caused acceleration), but inertia takes over from there. The only reason you need to keep pushing a real-world object, like a heavy box across the floor, is to fight against opposing forces like friction.

- Misconception: You have to keep pushing an object to keep it moving.

- Reality: An object in motion stays in motion. A net force is only required to make it speed up, slow down, or change direction.

Always Remember the Net Force

This last one is probably the most common mistake when it comes to the math. It’s so tempting to just grab one force you see in a problem and plug it into F = ma. But the "F" in Newton's second law is the net force—the vector sum of all the forces acting on the object.

Let's say you and a friend are pushing a box. You push to the right with 30 N of force, and your friend pushes to the left with 10 N. You can't just use 30 N or 10 N in the formula.

You have to find the overall, or net, force first:F_net = 30 N (right) - 10 N (left) = 20 N (right)

It’s this 20 N net force that actually determines the box's acceleration. Forgetting to add up all the forces is a surefire way to get the wrong answer.

If you can keep these three points straight—the difference between mass and weight, the real role of force, and always using the net force—you'll have a much stronger foundation for tackling any physics problem that comes your way.

Common Questions and Sticking Points

Even after you get the basics down, Newton’s Second Law can throw a few curveballs. Let's clear up some of the most common questions that trip students up.

Does Newton's Second Law Work for Everything?

For pretty much everything you'll encounter in daily life, yes. But it does have its limits. Once things start moving ridiculously fast—we're talking close to the speed of light—the familiar world of classical mechanics begins to warp.

At these insane speeds, Einstein's theory of special relativity comes into play. The object's mass actually seems to increase from our perspective, making it harder and harder to accelerate. You need to apply more and more force just to get a tiny bit more acceleration, so F=ma no longer gives the full picture.

How Is the First Law Different from the Second?

This is a fantastic question because they're two sides of the same coin. Newton's First Law (the law of inertia) tells you what happens when there's no net force: an object just keeps doing what it's doing. The Second Law then provides the blueprint for what happens the moment a net force is applied.

A great way to think about it is that the First Law is just a special case of the Second Law. If the net force (F) in F=ma is zero, then acceleration (a) must be zero. An object with zero acceleration is either sitting still or cruising at a constant velocity—which is exactly what the First Law says.

Where Does Friction Fit into All This?

Friction isn't some separate, mysterious thing; it’s just another force you have to account for in your net force calculation. It’s the force that always fights against motion (or attempted motion) between two surfaces.

For instance, say you push a heavy box with 50 N of force. If the force of friction is pushing back with 20 N, the actual net force that makes the box accelerate is only 30 N. That's the number you plug into F=ma. In the real world, you can almost never ignore friction.

Struggling with a physics problem or just need a concept explained differently? Feen AI is like having a tutor in your pocket. Snap a photo of your homework or type in a question to get step-by-step solutions for Physics, Chemistry, Math, and more. Stop staring at the page and get unstuck by visiting https://feen.ai to try it out.

Recent articles

Struggling with what is implicit differentiation? This guide uses simple analogies and clear examples to explain the concept, process, and common mistakes.

Struggling with what is momentum and impulse? This guide uses clear analogies and real-world examples to explain these core physics concepts simply.

Learn how to study for ACT Math with strategies that work. This guide covers smart prep, practice tests, and tips to raise your score.

Learn how to solve related rates problems with our practical guide. Get clear examples, expert tips, and a step-by-step framework to master calculus.

Discover how to study for AP Biology with our expert guide. Learn top strategies, study schedules, and practical tips to master the content and ace your exam.

Struggling with circuit homework? Learn the rules of voltage drop in a parallel circuit with simple analogies, clear formulas, and solved examples.