How to Solve Exponential Equations: A Clear, Click-Worthy Guide

Learn how to solve exponential equations with simple steps, clear explanations, and real examples.

When you're faced with an exponential equation, the path forward usually boils down to one of two core strategies: either get the bases to be the same, or bring in logarithms. Which one you pick isn't a matter of preference; it's dictated entirely by the structure of the equation in front of you.

Let's break down how to choose your approach and execute it flawlessly.

What Are We Even Solving?

Exponential equations might look a little scary at first, but they're just math's way of describing things that change really, really fast. Think about anything from compound interest in a savings account to the growth of a bacterial colony.

At its heart, an exponential equation is simply one where the variable you need to find—your 'x'—is tucked away in the exponent. A classic example is 3^x = 81. The whole game is about figuring out the right tool to isolate that variable.

This isn't some newfangled math, either. Humans have been grappling with exponential growth for thousands of years. We can go all the way back to ancient Egypt, around 1650 BCE, where scribes used the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus to solve very practical problems. They were figuring out things like grain supply logistics, which often involved geometric progressions—the very essence of exponential growth. They didn't have our neat x and y notation, but the fundamental understanding was there.

A Quick Look at the Core Methods

Before we dive deep, here's a quick overview of the main techniques we'll be covering. Think of this as your cheat sheet for deciding which tool to grab from your mathematical toolbox.

Core Methods for Solving Exponential Equations

| Method | When to Use It | Example Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Equating the Bases | When both sides of the equation can be easily rewritten with the same base number. This is the fastest method. | 2^x = 32 |

| Using Logarithms | When the bases cannot be matched. Logarithms are the universal key for bringing the exponent down. | 5^x = 17 |

| Substitution (U-Method) | For equations that look like quadratic equations but with exponential terms. | 4^x - 2^x - 12 = 0 |

| Numerical Methods | For highly complex equations where an exact algebraic solution isn't possible. | e^x = x + 2 |

This table gives you a bird's-eye view, but the real skill comes from recognizing these patterns in the wild.

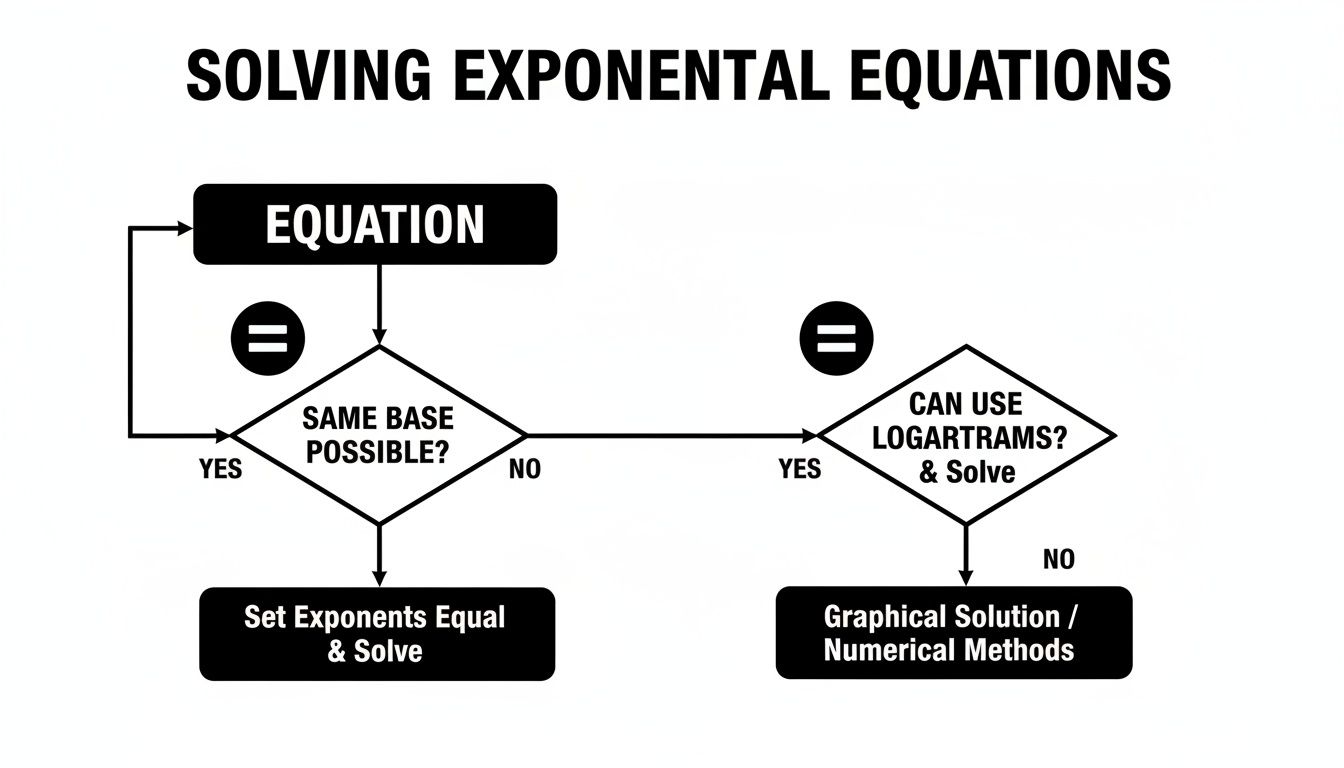

Your Path to the Solution

So, how do you know where to start? This decision tree gives you a clear visual guide.

As you can see, your first move should always be to check if you can rewrite both sides with a common base. If the answer is yes, you've found the shortcut. If not, don't worry—logarithms are your reliable go-to.

Making these ideas stick requires more than just reading. This is where tools like interactive simulations in STEM education become incredibly valuable, as they help connect the abstract formulas to tangible, visual outcomes.

Key Takeaway: In any exponential equation, the goal is to get the variable out of the exponent. You can either do this directly by making the bases equal, or you can use the power of logarithms to bring the exponent down to a level where you can solve for it.

The Same-Base Method: An Elegant Shortcut

Sometimes, the most direct path to a solution is finding a common language for both sides of an equation. That's the whole idea behind the same-base method. When you can get both sides of an exponential equation to share the same base number, you've found a powerful shortcut that lets you skip more complex tools like logarithms.

The logic is beautifully simple: if b^x = b^y, then it has to be true that x = y. As soon as the bases match, you can drop them and set the exponents equal to each other. This neat trick turns a tricky exponential problem into a straightforward algebra problem. The real challenge, then, becomes a bit of a puzzle: can you spot the common base that ties the numbers together?

This entire approach works because of the foundational rules of exponents, first explored by mathematicians like Archimedes and later standardized into the clean notation we use today by thinkers like René Descartes. It’s no surprise that 82% of high school curricula focus on these rules as a primary solving method—it’s intuitive and cuts down on common mistakes. If you're curious, you can explore the history of exponentiation to see how these concepts evolved.

How to Spot and Use Common Bases

The real skill here is training your brain to see numbers differently. When you look at 81, you shouldn't just see "eighty-one." You should see 3^4 or 9^2. Recognizing these relationships instantly is the key to mastering this method.

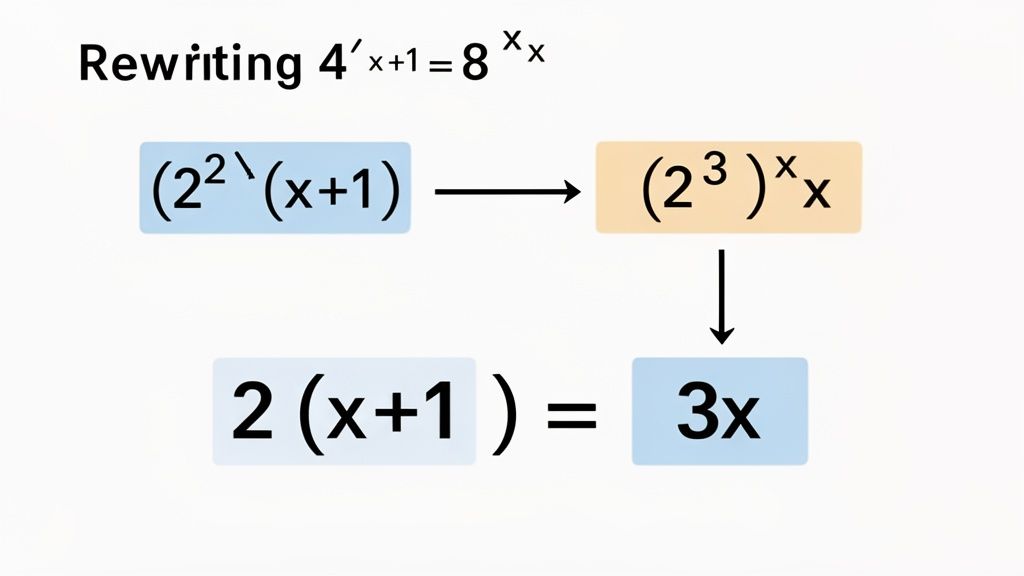

Let’s walk through a classic example: 4^(x+1) = 8^x.

Find the common ground: At first glance, the bases are 4 and 8. They're different, but they share a common root: they're both powers of 2. We know that 4 = 2^2 and 8 = 2^3.

Rewrite the equation: Now, let's substitute those back into our problem. This transforms it into (2^2)^(x+1) = (2^3)^x.

Simplify the exponents: Remember the power-of-a-power rule, which says (a^m)^n = a^(mn). Applying that to both sides, we get 2^(2x+2) = 2^(3x).

Equate the powers: Look at that—the bases are now identical. We can confidently set the exponents equal to each other: 2x + 2 = 3x.

Solve for x: A quick bit of algebra shows us that x = 2. Done.

Pro Tip: Keep a small cheat sheet of common powers for bases like 2, 3, 5, and 10. Knowing off the top of your head that 8 is 2^3, 27 is 3^3, and 625 is 5^4 will make you much, much faster at solving these problems.

Using Logarithms When Bases Don't Match

The same-base method is a slick trick when it works, but what happens when you’re staring down an equation like 5^x = 42? You can try all day, but you'll never be able to rewrite 42 as a nice, clean power of 5.

This is exactly the kind of problem that logarithms were made for. They are your go-to tool when the bases just won't cooperate.

Think of a logarithm as the perfect counterpart to an exponent. It’s designed to answer the question, "What power do I need to raise a base to, to get this specific number?" This inverse relationship is what lets us "unlock" a variable that's stuck up in an exponent. To really wield this tool effectively, you first need a solid grasp of the definition of logarithm.

The Power Rule: Your Key to Freedom

The real magic behind using logarithms here comes down to one critical property: the power rule. It’s a game-changer.

The rule states that log(b^x) = x * log(b). See what happened? The exponent (x) is no longer an exponent—it’s been brought down to the front as a simple coefficient. Your variable has been freed.

This transformation is our core strategy. By taking the logarithm of both sides of an equation, you can use the power rule to turn a tricky exponential problem into a straightforward linear equation that’s much easier to solve.

To make things even clearer, here are the essential logarithm properties you’ll be leaning on.

Logarithm Properties Cheat Sheet

This little table is a great reference for the rules that help us simplify and solve these equations.

| Property Name | Rule | How It Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Product Rule | log(xy) = log(x) + log(y) |

Breaks down a complex log of a product into two simpler logs. |

| Quotient Rule | log(x/y) = log(x) - log(y) |

Simplifies a log of a fraction into the difference of two logs. |

| Power Rule | log(b^x) = x * log(b) |

The most important one! It lets you bring the exponent down to solve for it. |

| Change of Base | log_b(x) = log(x) / log(b) |

Allows you to calculate any base log using the log or ln on your calculator. |

Keep these rules handy. The Power Rule is the star of the show for solving exponential equations, but the others are crucial for simplifying expressions before you get to the final steps.

Common Log vs. Natural Log: Which One to Use?

Once you decide to take the log of both sides, your calculator gives you two main options: the common logarithm (log, which is base 10) and the natural logarithm (ln, which is base e).

Which should you choose?

- Common Log (log): This is your base-10 logarithm. It's a reliable, all-purpose choice that works for nearly any equation.

- Natural Log (ln): This one is base e (Euler's number, roughly 2.718). You should always reach for

lnwhen your equation involves the constant e.

Back in 1683, Jacob Bernoulli stumbled upon the constant e while figuring out continuous compound interest. It was a massive discovery because e turned out to be the natural base for describing all sorts of change, from population growth to radioactive decay. Today, e is the foundation for over 90% of continuous growth models in fields like physics and economics.

The Takeaway: For most problems that don't involve e, it honestly doesn't matter which one you use. Both

logandlnwill get you the same correct answer. The key is to be consistent—use the same log on both sides of the equation. Many people just default tolnout of habit from their calculus days.

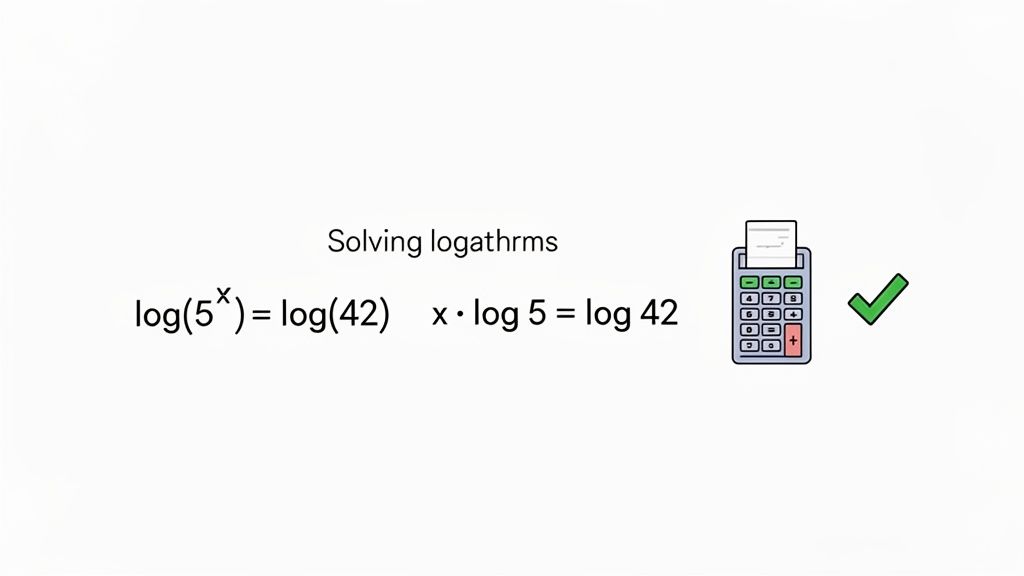

Let’s circle back to our original problem, 5^x = 42, and solve it using the natural log.

First, take the

lnof both sides. This keeps the equation balanced.ln(5^x) = ln(42)Next, apply the power rule. Bring that

xdown in front.x * ln(5) = ln(42)Now, isolate

x. Just divide both sides byln(5).x = ln(42) / ln(5)Finally, grab your calculator. You’ll find

x ≈ 3.737 / 1.609, which gives you a final answer of x ≈ 2.322.

And there you have it. By following this simple, repeatable process, we systematically solved an equation that was impossible to tackle with the same-base method. This same logic works for even more complex problems, proving just how powerful logarithms are for taming exponents.

If you're curious about how this works in reverse, our guide on https://feen.ai/blog/how-to-solve-logarithmic-equations provides a great look at the other side of the coin.

Advanced Strategies for Tricky Equations

Sooner or later, you'll run into an exponential equation that doesn't fit the basic templates. These problems might look strange at first, but don't panic. They usually just require a bit more creativity.

The real skill here is learning to recognize the underlying structure of the equation. Often, a complicated-looking problem is just a familiar type of equation wearing a clever disguise.

Handling Quadratics in Exponential Form

Let's look at an equation like 4^x - 2^x - 12 = 0. Right away, you can see that you can't just equate the bases or easily isolate x.

The trick is to spot the relationship between the bases. Notice that 4 is just 2^2. That means we can rewrite 4^x as (2^2)^x, which is the same as (2^x)^2.

Suddenly, our equation looks very different: (2^x)^2 - 2^x - 12 = 0.

If you squint a little, that structure should look familiar. It mirrors the classic quadratic form ay² + by + c = 0. We can make this concrete by using a technique called u-substitution.

- Make the substitution: Let a new variable, u, equal 2^x.

- Rewrite the equation: Swapping in u transforms the problem into u² - u - 12 = 0.

- Solve the quadratic: Now we're on solid ground. This is a simple quadratic that factors neatly into (u - 4)(u + 3) = 0. This gives us two possible values for u: u = 4 and u = -3.

Of course, we're not done yet. We need to find x, not u. So, we substitute back.

For u = 4: We get 2^x = 4. By inspection, you can see that x = 2.

For u = -3: We get 2^x = -3. This is where you have to pause and think. A positive number like 2 raised to any real power can never be negative. It's impossible. So, this path leads to no real solution.

The only valid answer is x = 2. This substitution method is a fantastic tool for simplifying what seems like an unsolvable problem. For a deeper dive, check out our guide on how to solve quadratic equations.

When Variables Appear on Both Sides

What happens when you have variables in the exponents on both sides of the equation, like in 3^(x+2) = 7^(x-1)? The bases are different, and there's no obvious way to make them the same. This is a prime job for logarithms.

The strategy is to take the logarithm of both sides. You can use any base, but the natural log (ln) is usually the cleanest choice.

ln(3^(x+2)) = ln(7^(x-1))

Now we can use the power rule of logarithms, which lets us bring those exponents down in front. This is the key step that gets the variable out of the exponent.

(x + 2)ln(3) = (x - 1)ln(7)

From here, it’s just algebra. We have a standard linear equation, so we distribute the log terms.

x*ln(3) + 2*ln(3) = x*ln(7) - ln(7)

Next, group all the terms with x on one side and the constant terms (the logs without x) on the other.

2*ln(3) + ln(7) = x*ln(7) - x*ln(3)

Finally, factor out the x and solve for it.

2*ln(3) + ln(7) = x(ln(7) - ln(3))

x = (2*ln(3) + ln(7)) / (ln(7) - ln(3))

You can punch that into a calculator to get the decimal approximation, which comes out to x ≈ 4.93.

Key Insight: Many complex exponential equations are just simpler problems in disguise. Whether it's a hidden quadratic or a problem needing logarithms, the goal is always the same: transform it into a solvable algebraic form you already know how to handle.

Sidestepping Common Pitfalls

Working with exponents and logarithms can be tricky. It's surprisingly easy to make a small error that throws your entire answer off. I've seen it countless times—the same mistakes pop up again and again on homework and exams.

The good news is that once you know what to look for, you can learn to avoid these traps altogether. Let's walk through the most common blunders I see students make so you can spot them and stay on track.

Mixing Up Logarithm Properties

Logarithm rules are powerful, but they have to be applied exactly as they are written. The most frequent mistake is trying to get creative with them, especially when a log contains a sum or difference.

This is the big one:

- Wrong:

log(x + y) = log(x) + log(y) - Right:

log(x * y) = log(x) + log(y)

It's an easy mistake to make—it just looks like it should work. But the logarithm of a sum, log(x + y), cannot be broken apart. If you see a plus or minus sign inside a logarithm, that's a red flag. You're likely dealing with an expression that can't be simplified further with that rule.

Another one I see often is misapplying the power rule. We know that log(x^n) is the same as n * log(x). But people sometimes try to apply that logic to (log(x))^2. These are two completely different things. The first is log(x) * log(x), while the second is just 2 * log(x). Be mindful of where the exponent is—is it on the x or on the entire log?

Small Slips in Algebra and Calculator Use

Honestly, sometimes the most maddening errors have nothing to do with the logs themselves. They're just simple algebraic slip-ups that sneak in and derail an otherwise perfect solution.

Here are a few classic examples:

- Distribution errors: In an equation like

(x - 2)log(5) = x*log(3), it’s so easy to multiplylog(5)byxbut completely forget to also multiply it by -2. - Losing a negative sign: A misplaced or dropped negative sign is probably the single most common source of wrong answers in all of algebra. It's a tiny detail that makes a huge difference.

- Calculator typos: When you're ready for the final calculation, like

x = ln(20) / ln(4), make sure you're typing it in correctly.ln(20)/ln(4)is a totally different number thanln(20/4). Close those parentheses!

Your Best Defense: Always Check Your Work Here’s the single best piece of advice I can give you: plug your final answer back into the original equation. It takes an extra minute, but it’s the ultimate safety net. If the left side equals the right side, you can be 99% sure you got it right. If not, you've caught a mistake and can go back and hunt it down. This one habit will save you from almost every error, from log property mix-ups to simple calculation mistakes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Even after you've got the methods down, some specific questions always seem to come up when you're wrestling with these problems. Let's walk through a few of the most common ones I hear, so you can tackle any exponential equation with confidence.

When Should I Use Natural Log vs. Common Log?

This is a great practical question. Technically, you can use either the natural log (ln) or the common log (log) for most problems, but there’s a smart way to choose.

My rule of thumb is this: use the natural log (ln) whenever your equation involves the number e (Euler's number). If you have an equation like 5e^(2x) = 20, taking the natural log of both sides makes life so much easier. The ln(e^(2x)) part simplifies directly to 2x. It's a clean, direct move because ln(x) is just log base e, making it the perfect inverse for e raised to a power.

For any other base, like in 4^x = 15, it really doesn't matter. You can use either log or ln. A lot of people, especially those who've taken calculus, just default to using ln out of habit. The only hard rule is to be consistent—whatever you do to one side, you have to do to the other.

Can an Exponential Equation Have No Solution?

Absolutely. It's totally possible for an exponential equation to have no real solution, and it usually happens when the math leads you to an impossible statement.

The classic example is an equation like 2^x = -4. Just think about what that means. The base, 2, is positive. No matter what real number you plug in for x, raising a positive number to that power will always give you a positive result. There's simply no real value of x that can make 2^x turn into a negative number or zero.

If you were to push forward with logarithms, you’d end up with x = log₂(−4), which is undefined for real numbers. When you hit a wall like this, it’s a clear sign that no real solution exists.

Key Takeaway: An expression like

b^x, wherebis a positive number, can never equal zero or a negative number. If your equation simplifies to this form, you've found a problem with no real solution.

How Do I Solve Equations with Exponents on Both Sides?

When you run into an equation with variables in the exponents on both sides, something like 5^(x-1) = 2^(x+3), logarithms are going to be your best friend. The bases (5 and 2) are different, and you can't easily make them match, so taking the log of both sides is the only way forward.

Here’s the game plan:

Apply the log to both sides. It doesn't matter if it's common log or natural log, just be consistent.

log(5^(x-1)) = log(2^(x+3))Use the power rule. This is the key step. Bring those exponents down in front as multipliers.

(x-1)log(5) = (x+3)log(2)

Suddenly, what looked like a complicated exponential problem is now a standard linear equation. From here, it's just algebra: use the distributive property, get all your x terms on one side, factor out the x, and solve. It's a few more steps, but the principle is straightforward. If you want to see this in action, you can work through more examples with an AI math solver to really get the hang of it.

When you're stuck on a tricky problem, getting a clear, step-by-step explanation can make all the difference. Feen AI is designed to be your go-to homework helper, offering instant support in Math, Physics, Chemistry, and more. Just upload a picture of your problem, and get the answers you need to keep moving forward. Check it out at https://feen.ai.

Relevant articles

Boost your skills with quadratic formula practice problems: 8 focused questions to reinforce steps, discriminants, and solving.

Struggling with absolute value? Learn how to solve absolute value equations with our guide, packed with clear examples, common pitfalls, and real strategies.

Struggling with how to graph inequalities? This guide breaks it down with clear steps for number lines, coordinate planes, and real-world examples.

Learn how to solve quadratic equations using simple methods like factoring, the quadratic formula, and more. Get clear examples and expert tips for any problem.

Learn how to factor polynomials completely using our guide. From GCF to advanced methods, we'll help you solve any algebra problem with confidence.