How to write a lab report conclusion: A concise guide to top grades

Learn how to write a lab report conclusion with a clear structure, real examples, and tips to boost your grade.

Your lab report conclusion is where you bring everything together. It’s more than just a summary; it’s your final opportunity to demonstrate that you truly understand the experiment's significance, connecting your data back to the core scientific principles you were investigating.

Why Your Conclusion Is the Most Important Part of Your Lab Report

It's easy to treat the conclusion as a quick wrap-up, something you rush through after all the hard work of the experiment is done. But from an instructor's perspective, this section is often the most revealing part of your entire report. This is where you stop just presenting data and start interpreting it, which shows a much deeper level of understanding.

A great conclusion elevates your report from a simple record of what you did into a compelling scientific narrative. You’re connecting the dots for your reader, explaining why your results are meaningful and where they fit within the bigger picture of your field. It's less about repeating what happened and all about proving what you learned.

The Make-or-Break Section for Your Grade

Let’s imagine you just finished a chemistry experiment on how temperature affects reaction rates. Stating that "the reaction was faster at higher temperatures" is a result. A strong conclusion, however, would dig deeper, linking this observation to collision theory and explaining that increased kinetic energy causes molecules to collide more frequently and with greater force.

That analytical leap is exactly what separates a good grade from a great one. It’s the final and most important moment where you engage with the fundamental ideas of the scientific method. For a refresher on these core principles, check out our guide on the 7 steps of the scientific method.

The conclusion isn't just a recap—it's where you synthesize information, evaluate your experiment, and prove your scientific understanding. It’s the intellectual heavy lifting that justifies your entire experiment.

Skimping on your conclusion can seriously hurt your grade. In a survey of over 5,000 STEM undergraduates, a staggering 68% pointed to poorly written conclusions as the main reason their reports scored below a B. You can find more insights on effective lab report writing in academic skills guides. That number says it all: a weak finish can completely undermine all the effort you poured into the lab work itself.

The Anatomy Of A High-Scoring Conclusion

So you’ve run the experiment, crunched the numbers, and written up everything else. It can be tempting to rush through the conclusion, but honestly, this is where you seal the deal. A great conclusion doesn’t just rehash what you did; it gives your entire experiment meaning, transforming all that raw data into a convincing scientific argument.

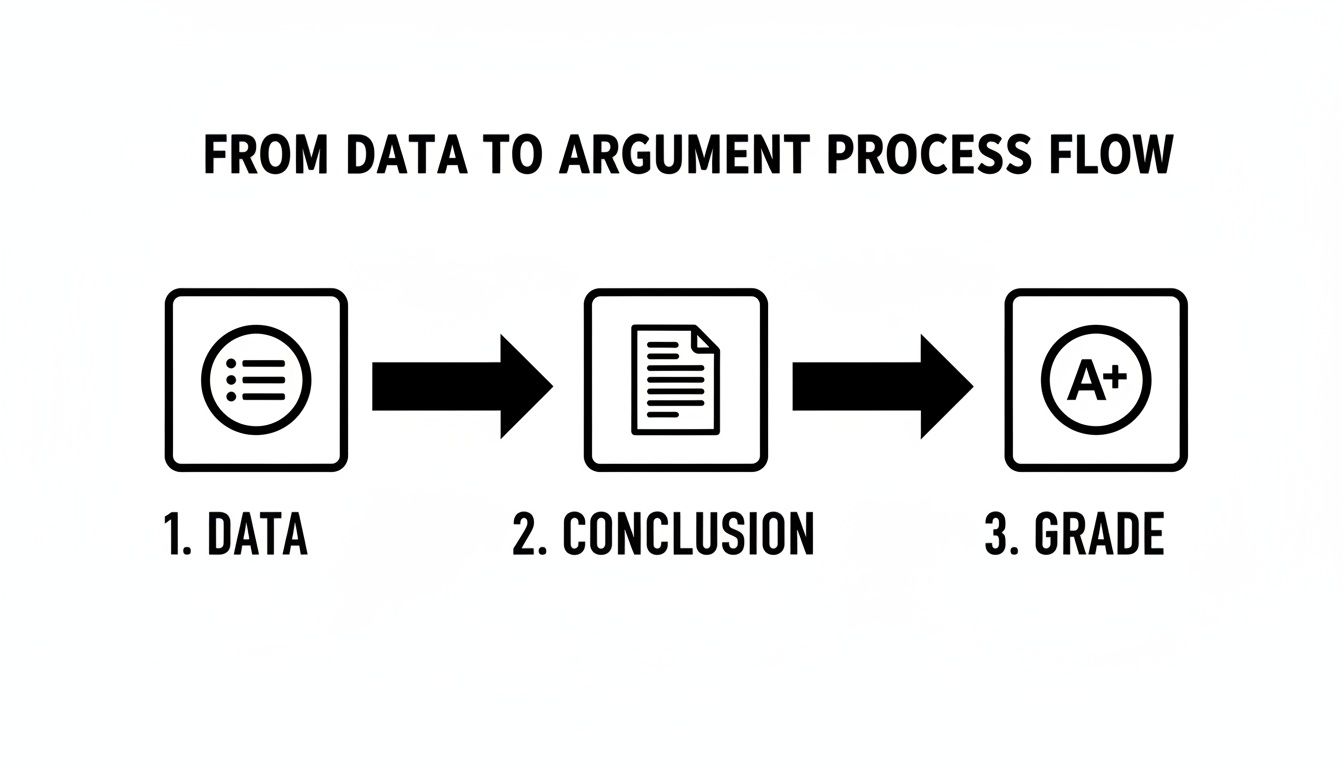

Think of it this way: a powerful conclusion is built on four key pillars. They create a simple, logical flow that walks your reader from the initial question to your final takeaway. If you skip one, the whole structure feels shaky and your report loses its impact.

The journey from messy data to a clear, persuasive conclusion is what gets you a good grade.

This diagram perfectly illustrates how the conclusion is the critical bridge connecting your hard work in the lab to academic success. Let's break down how to build that bridge, piece by piece.

A well-crafted conclusion follows a proven structure that addresses four essential questions. I've laid them out below in what I call the "Four Pillars" of a strong conclusion. Getting these right is the key to demonstrating you didn't just follow instructions—you understood the science behind them.

The Four Pillars of a Strong Conclusion

| Component | Purpose | Example Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Revisit Hypothesis | To directly answer the initial research question. | "The results supported the hypothesis that..." |

| Summarize Key Data | To provide concrete evidence for your claim. | "...as shown by the 45% increase in..." |

| Analyze and Interpret | To explain the "why" behind your results using scientific principles. | "This aligns with the theory of..." |

| Discuss Limitations | To acknowledge potential errors and suggest future work. | "A potential source of error was... A future study could..." |

By methodically addressing each of these components, you ensure your conclusion is comprehensive, convincing, and demonstrates a deep understanding of the experiment.

Revisit And Restate Your Hypothesis

Jump right in by reminding the reader what you set out to prove. Start your conclusion with a clear, direct restatement of your original hypothesis. This immediately brings the reader back to the central purpose of your lab.

Next, you need to deliver the verdict. Did your results support or refute the hypothesis? Be decisive. Vague phrasing like "it seems like the hypothesis was correct" sounds weak. A much stronger statement is, "The data collected supports the hypothesis that..."

This direct claim acts as the thesis for your conclusion, framing everything that follows as the evidence backing it up.

Summarize Key Findings With Data

Now it's time to show your proof. You've made a claim about your hypothesis; back it up with the most important numbers from your results section. This isn't about dumping all your data here again. Instead, strategically select the key values that most powerfully support your conclusion.

For example, if you were testing enzyme activity at various temperatures, you'd pinpoint the most significant finding. You might write: "The enzyme showed peak activity at 40°C, with an average reaction rate of 0.8 units/minute, a full 45% higher than the rate observed at 20°C."

See how that works? Using specific, hard data makes your argument undeniable and reinforces that your experiment was a success.

Analyze And Interpret The Results

Here's where you get to show off your brain. You’ve presented the what (your data); now you need to explain the why. What do these numbers actually mean in the context of scientific theory? This is your chance to connect your findings back to the concepts you discussed in your introduction. Why did the enzyme activity peak at that specific temperature, anyway?

This part of your conclusion is all about critical thinking. You could explain it like this: "The peak activity at 40°C aligns with established kinetic theory, where increased thermal energy leads to more frequent and forceful collisions between the enzyme and its substrate."

This analytical step is precisely what instructors look for. It’s not enough to say what happened; you must explain the scientific mechanism behind why it happened. This is your chance to show you’ve learned something meaningful.

Don't just take my word for it. One large-scale study tracked 12,000 students and found that those who explicitly included "what was learned" statements in their conclusions boosted their science grades by an average of 22%. You can dig into more of the data from this educational research on report writing.

Discuss Errors And Future Directions

No experiment is perfect, and every good scientist knows it. Acknowledging the limitations of your work doesn't weaken your report—it strengthens it by showing you have a realistic understanding of the scientific process.

Be specific about potential sources of error. Instead of a lazy phrase like "human error," point to something concrete like "inconsistent timing of measurements" or "a potential for cross-contamination between samples."

Finally, end on a forward-looking note. What’s next? Based on what you found, what's a logical follow-up experiment? Maybe you could test a wider range of temperatures or use a different type of enzyme. Proposing a next step shows you’re already thinking like a scientist.

Seeing It in Action: Real Lab Report Conclusion Examples

Let's be honest, all the rules and templates in the world can't beat a good example. Seeing how these pieces fit together in a real conclusion is often what makes everything click.

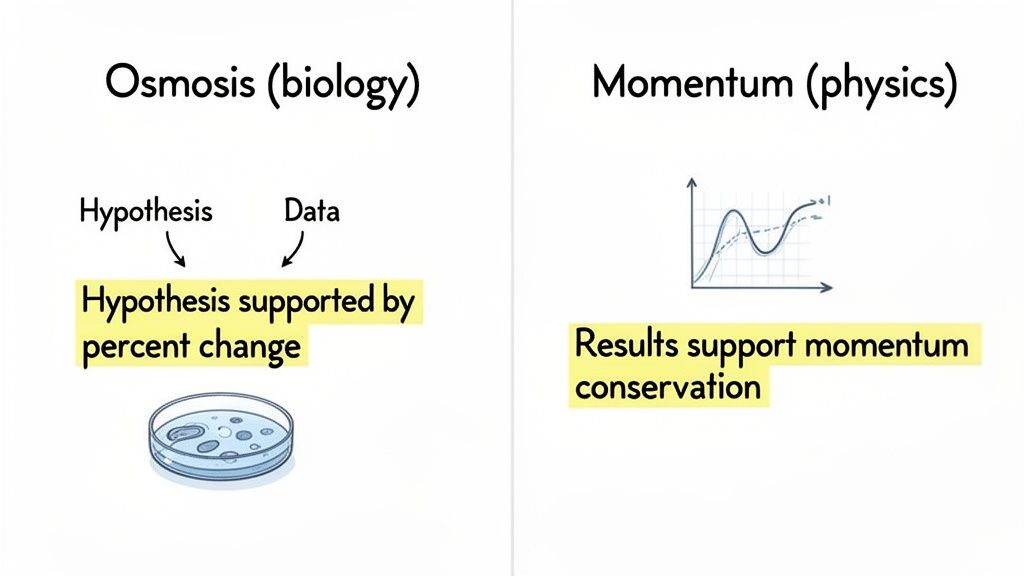

To bridge that gap between theory and what you actually need to write, we’ll break down two different conclusions. We'll start with a classic high school biology experiment and then move on to a common college-level physics lab.

By looking at these side-by-side, you'll see how the core components—restating the hypothesis, summarizing key data, explaining the results, and talking about what went wrong—create a strong, convincing final paragraph.

Notice how a well-written conclusion flows logically. It doesn't need to be long; it just needs to be clear, direct, and packed with the essential information.

High School Biology Example: Osmosis in Potato Cells

First up, an experiment you've probably done or will do soon. For more tips on putting together reports like this, check out our full guide on the standard biology lab report format.

- Lab Context: The experiment aimed to see how different sucrose solutions (0%, 1%, 5%, and 10%) affected the mass of potato cores. The hypothesis predicted that potato cores in higher sucrose concentrations would lose mass, while those in pure water would gain it.

Example Conclusion:

The results of this experiment supported the hypothesis that potato cores lose mass in hypertonic sucrose solutions and gain mass in a hypotonic one. The key finding was a 12.4% average decrease in mass for cores in the 10% sucrose solution, compared to an 8.2% average mass increase in distilled water (0% solution). This aligns with the principles of osmosis, as water moved from the potato cells (higher water potential) into the surrounding high-concentration solution.

A likely source of error was inconsistent blotting of the potato cores before the final weighing, which may have left excess water and slightly skewed the mass measurements. For a future experiment, it would be interesting to test more granular sucrose concentrations to pinpoint the exact isotonic point for these potato cells.

College Physics Example: Conservation of Momentum

Now let's ramp up the complexity a bit with a typical introductory physics lab.

- Lab Context: This lab used an air track and two gliders to test the conservation of linear momentum during an inelastic collision. The hypothesis stated that the system's total momentum would be conserved right before and after the gliders collided.

Example Conclusion:

The experimental data confirms the hypothesis that linear momentum is conserved in an inelastic collision. We calculated the total initial momentum of the system to be 0.452 kg·m/s and the total final momentum to be 0.441 kg·m/s. This difference of only 2.4% falls well within the accepted margins for experimental uncertainty.

This outcome is consistent with Newton's Third Law, where the net change in momentum is zero due to equal and opposite internal forces. The primary source of error was likely residual friction from the air track, which acted as a small external force and caused the slight drop in the final momentum. To improve this, a future experiment could employ a more sensitive photogate system to reduce timing errors when measuring velocity.

Common Mistakes That Can Cost You Points

Even a conclusion that seems well-structured on the surface can lose points if it falls into a few common traps. I’ve seen these mistakes trip up students time and time again. Knowing what not to do is just as critical as knowing what to include, so let's walk through the most frequent errors I see when grading reports.

The absolute biggest mistake? Introducing new information. Your conclusion is for wrapping things up, not for bringing up new data or ideas for the first time. If you suddenly realize you forgot to mention a key measurement, go back and put it in the results section where it belongs. The conclusion should only analyze what you've already presented.

Vague and Weak Language

Another surefire way to weaken your entire report is to use imprecise, wimpy language. Phrases like "the experiment was a success" or "the results were pretty good" are scientifically meaningless. They tell your instructor nothing.

You need to be specific about why it was a success by tying it directly to your hypothesis and your data.

Just look at the difference here:

- Before: The experiment worked well and proved our theory.

- After: The data strongly supported our hypothesis, as evidenced by the 25% reduction in reaction time, which aligns with theoretical predictions.

See how much more powerful the second version is? It swaps a vague opinion for a confident, evidence-based claim backed by a hard number. That's what science is all about.

A great conclusion is your final, confident argument based on solid evidence. If you use weak or unclear language, it undermines the authority of your entire report and makes it seem like you're not even sure about your own findings.

Forgetting to Address the Hypothesis

This one feels obvious, but you'd be shocked how many lab reports I've graded where the student never actually says what happened with their hypothesis. Was it supported? Was it refuted? Were the results inconclusive? Your conclusion must give a direct answer to this question—it's the whole reason you did the experiment in the first place.

On the other end of the spectrum is being too long-winded. In science writing, quality beats quantity every single time. A College Board analysis of over 8,500 AP Science exams found that 74% of the top-scoring reports had conclusions under 150 words. They were direct and impactful. Compare that to the lower-scoring reports, where only 19% kept it that concise. You can learn more about how brevity and clarity lead to better scores.

Ignoring Errors or Making Excuses

Finally, don't pretend your experiment was perfect. Every experiment has limitations and potential sources of error. Acknowledging them doesn't mean you failed; it shows you have a mature understanding of the scientific process.

But please, avoid the generic excuse of "human error." It’s a cop-out. Instead, pinpoint specific issues, like "inconsistent timing of measurements due to manual stopwatch use," and briefly explain how that might have skewed your results. This kind of self-reflection demonstrates critical thinking—a skill every science instructor is looking for.

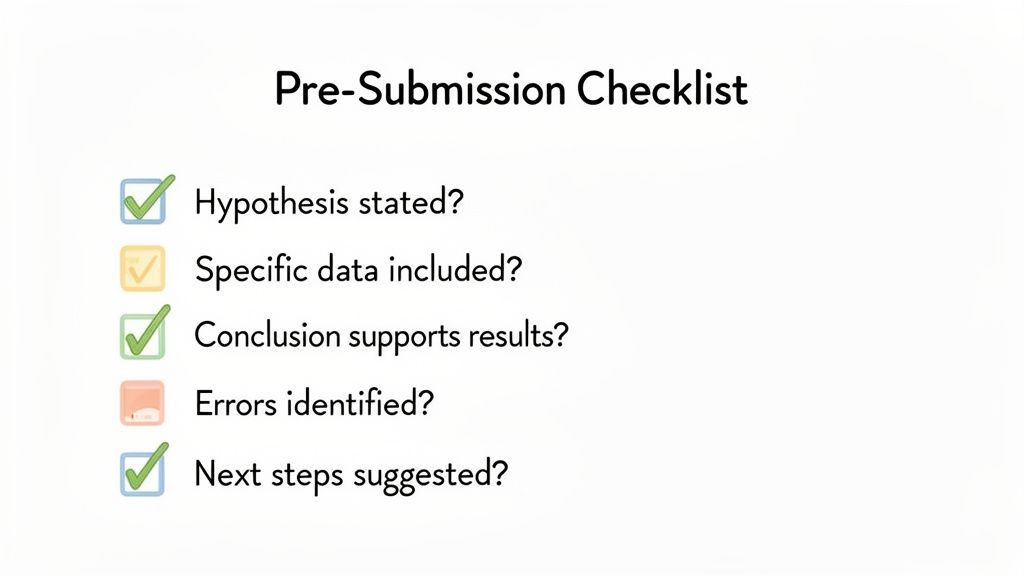

Your Pre-Submission Checklist for a Perfect Conclusion

Alright, before you hit 'submit,' let's do one last pass. This isn't about a full rewrite; think of it as a final polish to catch those small mistakes that can cost you easy points. Putting on your "grader" hat for just a few minutes can make a huge difference in your final mark.

Use these questions to look at your conclusion with a critical eye. They're designed to check for the exact things I, and other instructors, look for.

Critical Questions to Ask Yourself

If you can confidently say "yes" to each of these, you’re in great shape.

Did I directly state what happened with my hypothesis? This should be front and center. A clear statement like, "The data supported the hypothesis," is the perfect starting point. No need to be coy about it.

Is my claim backed by actual data from the lab? Vague statements are a red flag. Don't just say the results were significant—prove it. Point to your key findings, like "a 15% increase in reaction rate" or "a final momentum of 0.51 kg·m/s."

Have I explained why the results turned out this way? This is where you really show your understanding. You need to connect your data back to the core scientific principles you talked about in your introduction. This proves you get the theory, not just the lab procedure.

Did I identify a plausible source of error? Every experiment has limitations. Pointing one out shows you're thinking critically. But be specific! Instead of blaming "human error," mention something concrete like, "Slight temperature fluctuations in the lab may have affected..."

Is my language clear and confident? Now’s the time to sound like you know what you’re talking about. Ditch weak phrases like "it seems that" or "I think." Use strong, direct language. Good transition words for conclusions can also help your sentences flow together more naturally.

To wrap it all up, I've put together a quick table that boils these ideas down into a simple "Do vs. Don't" format. Keep it handy as you do your final review.

Do vs. Don't in Your Conclusion

| What to Do | What to Avoid |

|---|---|

| Directly state if your hypothesis was supported or refuted. | Leaving the reader to guess the outcome of the hypothesis. |

| Use specific data and numbers to back up your claims. | Making vague statements like "the results were good." |

| Connect your findings to established scientific theories. | Simply restating the results without any interpretation. |

| Identify a specific, realistic source of experimental error. | Blaming generic causes like "human error." |

| Write with clear, confident, and concise language. | Using weak or uncertain phrases like "we believe" or "it might be." |

| Propose a logical next step or a future experiment. | Introducing completely new ideas or hypotheses. |

At the end of the day, a strong conclusion leaves no doubt about what you accomplished and what you learned. It’s your final chance to prove you’ve mastered the material. This quick check helps make sure you stick the landing.

Got Questions About Lab Report Conclusions? We've Got Answers.

Even after you've drafted what feels like a solid conclusion, a few nagging questions can still bubble up. It's totally normal to have some last-minute doubts before hitting "submit." Let's walk through some of the most common sticking points students run into so you can hand in your paper with confidence.

Getting these final details right can be the difference between a good grade and a great one.

How Long Should My Conclusion Be?

This is easily the most popular question, and the answer is refreshingly simple: keep it concise. Your conclusion should be a powerful summary, not a drawn-out rehash of your entire experiment.

A good rule of thumb is to aim for one well-crafted paragraph, typically around 5-7 sentences or 100-150 words. Some instructors might have their own rules, so always check your assignment sheet first. But in general, brevity is your best friend. The goal is to be direct and impactful, not to fill space.

A study of thousands of AP science exams showed that top-scoring reports almost always had conclusions under 150 words. It’s proof that a short, focused conclusion packs a bigger punch than a long, rambling one.

What's the Difference Between the Results and the Conclusion?

This is a critical distinction that trips up a lot of students. The easiest way to think about it is this: your Results section is the what, and your Conclusion is the so what.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Results: This section is all about presenting your raw data objectively. You state the facts and figures exactly as you observed them, often using tables and graphs to make them clear. There's no interpretation here—just the numbers.

- Conclusion: This is where you actually interpret those numbers. You explain what the data means in the context of your original hypothesis, connect your findings to established scientific principles, and discuss the bigger picture.

In short, your results are the evidence, and the conclusion is the argument you build from that evidence.

Is It Okay to Say My Hypothesis Was Wrong?

Absolutely! In fact, you have to say it if your data doesn't support your initial prediction. Science isn't about being right all the time; it's a process of discovering the truth, whatever it turns out to be. A hypothesis is just an educated guess, not a guaranteed outcome.

Reporting that your hypothesis was refuted is not a failure. On the contrary, it demonstrates your scientific integrity. The key is to go a step further and explain why you think the results were different from what you expected. That kind of analysis shows a much deeper level of critical thinking than just confirming what you already thought.

How Many Sources of Error Should I Talk About?

You don’t need to list every tiny thing that could have possibly gone wrong. The best approach is to identify and discuss one or two significant sources of error that could have realistically skewed your data.

Focus on quality, not quantity. Instead of a long laundry list of minor issues, pick the most plausible error and thoughtfully explain its potential impact. For example, explaining how "a fluctuating room temperature may have altered enzyme reaction rates" is far more insightful than vaguely blaming "human error." This shows you’ve thought critically about the real-world limitations of your experiment.

Feeling stuck trying to word your findings or analyze your data? Feen AI can help you sharpen your lab report conclusion. Just paste in your draft, and our AI-powered homework helper can offer suggestions to make your language clearer, stronger, and more scientific. Check your reasoning and polish your writing to ensure you submit your best work at https://feen.ai.

Relevant articles

Learn how to write a strong argumentative essay with our guide. We cover building a thesis, using evidence, and structuring your argument for academic success.

Learn how to write a persuasive essay that wins arguments. Our guide covers crafting a strong thesis, finding solid evidence, and structuring your paper.

Learn how to cite sources in mla with clear examples for books, websites, and more. Write your paper confidently with MLA guidance.

Learn how to write a conclusion paragraph that leaves a lasting impression. Our guide covers proven structures, real examples, and mistakes to avoid.

Struggling with how to write a thesis statement? This guide breaks down the process with real examples and tips to craft a clear, arguable, and strong thesis.

Learn how to write research paper outline with our guide. Discover formats, structures, and revision tips to build a strong academic blueprint.