How to Solve Optimization Problems in Calculus The Definitive Guide

Learn how to solve optimization problems in calculus with our definitive guide. Master the techniques to find maximum and minimum values using real examples.

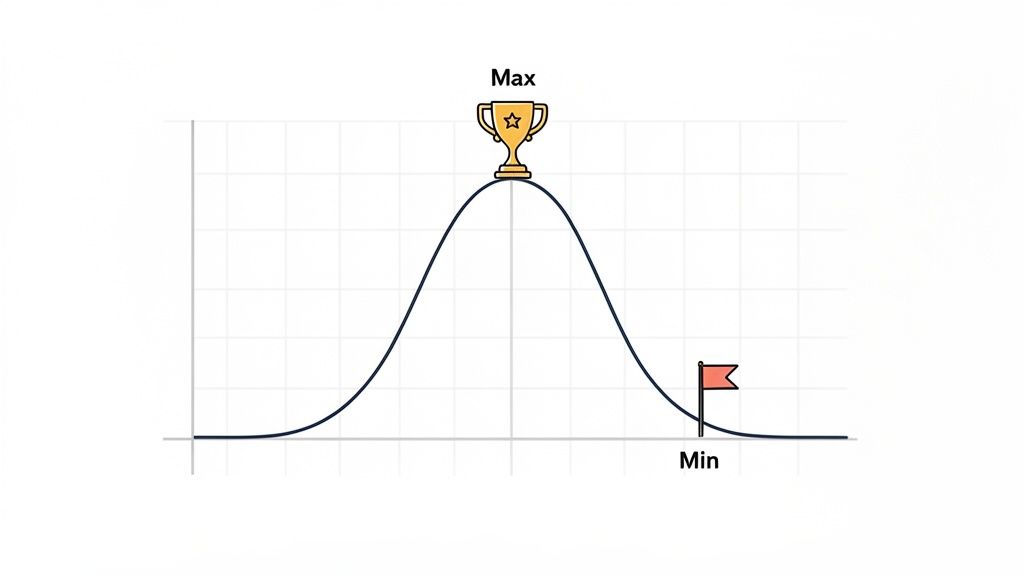

So, what does it mean to "solve an optimization problem" in calculus? In simple terms, you're using derivatives to find the absolute best-case scenario—the highest point (maximum) or the lowest point (minimum) of a real-world situation you've modeled with a function.

The whole game is about translating a practical goal, like getting the most profit or using the least amount of material, into a mathematical equation. From there, you hunt for the critical points where the function's rate of change is zero, which is where you'll find those peaks and valleys.

What Exactly Are Optimization Problems?

Let’s be real, the phrase "optimization problem" sounds way more complicated than it is. At its heart, it’s just about finding the best possible outcome given some limitations.

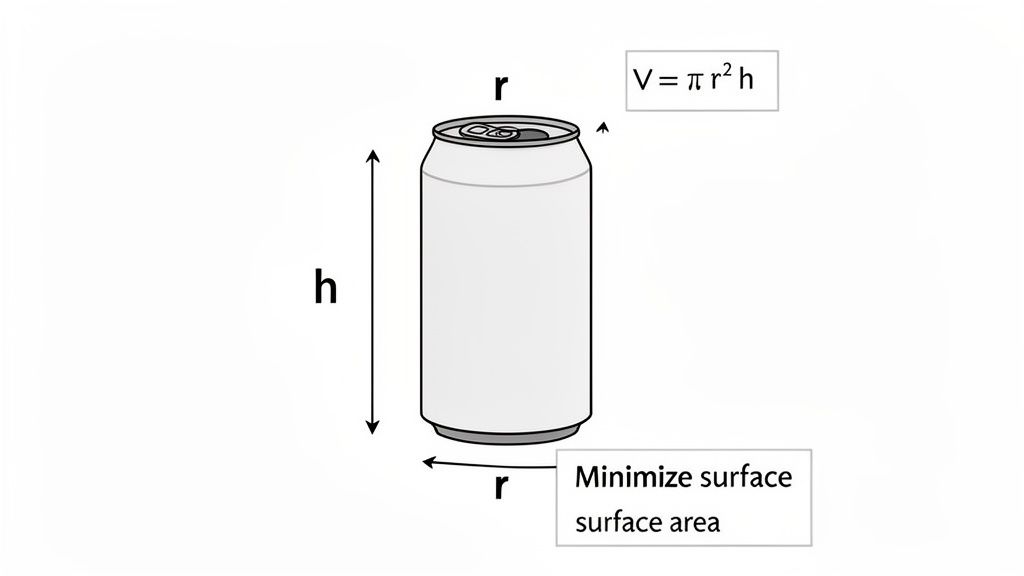

Think about it. A company wants to set the perfect price for a new gadget to maximize its revenue. An engineer needs to design a soda can that holds exactly 355 mL of liquid but uses the least amount of aluminum to cut costs. Both of these are classic optimization problems.

This is where calculus becomes your secret weapon. Derivatives are the tool we use to find the exact point where a function hits a peak and starts to go down (a maximum) or bottoms out before it starts to climb back up (a minimum). This is the secret to how to solve optimization problems in calculus. You’re basically looking for the "flat" spots on the function's graph, which is where the slope is zero.

A Quick Look at the History

This powerful method didn’t just appear out of thin air. The groundwork was laid back in the 17th and 18th centuries when calculus was born. Pioneers like Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz developed the concept of the derivative, which became the essential tool for finding these extreme points, or extrema. Understanding how these ideas were built over time shows just how fundamental they are to modern math and science.

The Two Key Parts of Any Optimization Problem

Before diving into the calculus, you first need to break down the word problem. Every single optimization problem you'll face has two crucial components:

- The Objective Function: This is the equation you're trying to maximize or minimize. It's the formula for the thing you care about, whether that's area, profit, volume, or distance.

- The Constraint: This is the limitation or rule you have to work within. It’s the boundary that keeps you from having an infinite answer, like only having 100 feet of fencing to work with or needing a box to hold a specific volume of 500 cubic inches.

The real art of solving these problems is learning how to translate a real-world scenario into these two mathematical components. Once you have the objective function and the constraint, the calculus becomes much more straightforward.

If you feel like your calculus fundamentals could use a tune-up before we go deeper, you might want to check out our guide on how to understand calculus.

Core Steps for Solving Optimization Problems

While every problem is unique, the strategy for solving them follows a reliable pattern. Here’s a quick overview of the process we'll be breaking down.

| Phase | Objective | Key Calculus Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | Translate the word problem into mathematical equations. | Algebra and Geometry |

| Calculus | Find the critical points where a max or min could occur. | Derivatives (First Derivative Test) |

| Verification | Confirm whether the critical point is a maximum, a minimum, or neither. | Second Derivative Test or Sign Analysis |

| Solution | Answer the original question using your verified result. | Substitution and Interpretation |

Think of this table as your roadmap. Nailing this systematic approach is the key to solving optimization problems confidently and correctly every time.

Translating Word Problems into Math

This is the moment. The point where the calculus seems straightforward, but staring at a paragraph of text makes your brain freeze up. Turning a story into a clean set of equations can feel like the hardest part of the problem, but it’s a skill you can master.

Think of yourself as a detective. You're reading through the word problem on a mission to find two key pieces of information hidden in the text: the objective function and the constraint. If you can successfully pull those two out, the rest is just a calculus exercise you already know how to do.

Identifying the Objective Function

The objective function is simply what you're trying to maximize or minimize. It's the whole point of the problem. Your first job is to scan the text for keywords that scream "optimization!"

Look for clues like:

- Largest or smallest

- Maximum or minimum

- Most or least

- Cheapest or fastest

These words point directly to your objective. If the problem asks for the "largest volume" for a box, your objective function is the formula for volume. If you need the "cheapest" fence, your objective is an equation for the total cost.

Let’s take a classic example. A company wants to make a soda can that holds a certain amount of liquid but uses the least amount of metal. That keyword "least" is your sign. The goal is to minimize the surface area of the can. So, your objective function is the formula for a cylinder's surface area.

Finding the Constraint Equation

Now for the second piece of the puzzle. The constraint is the rule you have to follow, the limitation that keeps the problem grounded in reality. Without a constraint, you could just make a container infinitely large or a cost infinitely small, which doesn't make much sense.

In our soda can scenario, the constraint is that the can must hold a specific volume, say 355 cubic centimeters. This isn't optional; it's a hard rule. This gives us our constraint equation: the formula for a cylinder's volume is set equal to that number. So, V = πr²h = 355.

This constraint is the magic link between your variables (in this case, radius r and height h). It’s what allows you to express one variable in terms of the other, which is crucial for the next step. You need to get your objective function down to a single variable before you can take the derivative.

Pro Tip: Before you even write a single equation, draw a picture. Seriously. A quick sketch of the box, can, or field, with all sides and dimensions labeled with variables like x, r, or h, can make the geometric relationships crystal clear. It’s the best way to avoid mixing up your formulas.

Once you have both the objective and the constraint written down, you've officially translated the word problem into math. If this is the part that always trips you up, you're not alone. It often comes down to strengthening your algebra fundamentals. For a quick tune-up, our guide on how to solve word problems in algebra can be a huge help.

Now, with your two equations in hand, you’re ready to use the constraint to simplify the objective and let the calculus begin.

Using Derivatives to Find Your Answer

Okay, you've done the setup work and have your objective function and constraints ready to go. Now it's time to unleash the power of calculus. This is where the abstract concepts you've been learning finally click into place to solve a real, tangible problem.

The whole process hangs on one fundamental idea: a function’s maximum or minimum value can only happen at its critical points.

Think of it this way: if you're at the very peak of a hill or the absolute bottom of a valley, the ground is momentarily flat. Those flat spots—where the slope is zero or undefined—are what we're looking for. Finding them is our first big move.

Finding Critical Points with the First Derivative

To hunt down these potential maximums and minimums, we turn to the first derivative. Remember, the derivative of a function is just a formula for its slope at any given point. To find where the slope is zero, we just need to take the derivative, set it equal to zero, and solve. It’s that straightforward.

Let's circle back to our soda can problem. Once you've used the volume constraint to write the surface area function using only one variable (the radius, r), you'll do this:

- Find the first derivative of the surface area function with respect to r.

- Set this new derivative equation equal to 0.

- Solve that equation for r.

The values you get for r are your critical points. These are the top candidates for the radius that will minimize the can's surface area. If you're a bit rusty on the mechanics, our guide on how to find the derivative of a function is a great refresher.

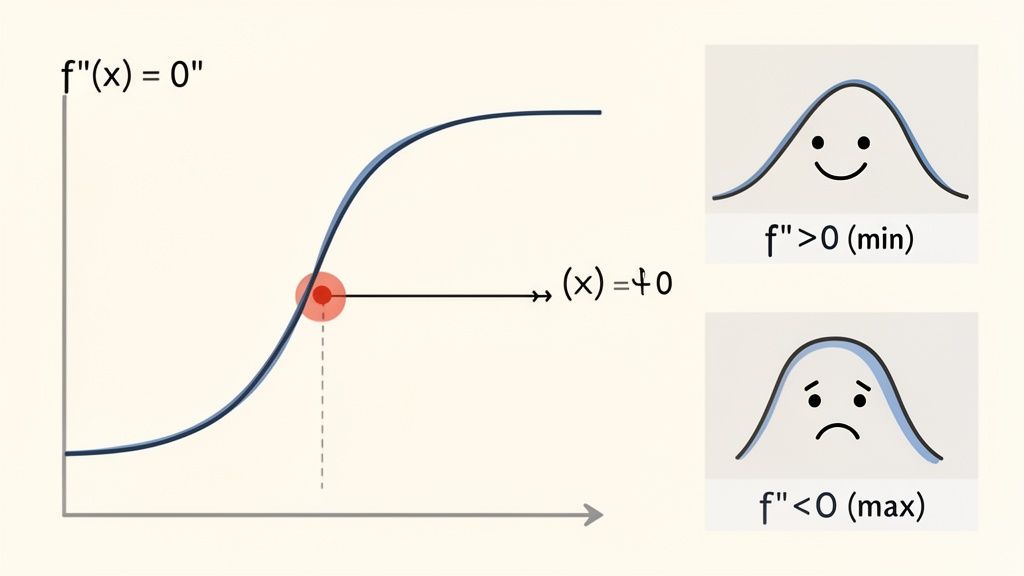

Verifying Your Answer with the Second Derivative Test

Finding a critical point is a huge step, but how can you be sure if it’s a maximum, a minimum, or just a weird flat spot that's neither? This is where the Second Derivative Test becomes your best friend. It’s a quick and elegant tool that tells you about the concavity—the curve—of the graph right at your critical point.

Here’s the game plan:

- Calculate the second derivative of your objective function.

- Plug your critical point into that second derivative.

- Look at the sign (positive or negative) of the result.

If the result is positive, the function is concave up (like a cup holding water), which tells you you've found a local minimum. If the result is negative, the function is concave down (like a frown), meaning you’ve found a local maximum.

A Simple Trick to Remember This

- A positive second derivative

(+)is like a smiley face:), which is concave up. The bottom of the smile is a minimum.- A negative second derivative

(-)is like a frowny face:(, which is concave down. The top of the frown is a maximum.

This little visual cue has saved me from making silly mistakes on exams more times than I can count.

Don't Forget to Check the Endpoints

Here’s one of the most common traps students fall into: forgetting the endpoints of the domain. Sometimes, the absolute maximum or minimum doesn't happen at a nice, clean critical point where the slope is zero. Instead, it occurs at the very edge of the possible values for your variable.

For example, say you're building a fence with a fixed amount of material. The length of one side can't be negative, and it also can't be longer than the total amount of fencing you have. These real-world limits create a closed interval, and you must check the boundaries.

Always finish your problem by doing a final check:

- Identify the logical endpoints for your variable (e.g., x must be between 0 and 10).

- Plug your critical points and the endpoint values back into the original objective function.

- Compare all the resulting values. The biggest one is your absolute max, and the smallest is your absolute min.

This last step ensures you've found the true, absolute answer for the given constraints, not just a local one. By combining these three tools—the first derivative, the second derivative test, and an endpoint check—you build a foolproof method for nailing optimization problems every single time.

Worked Example: Fencing a Rectangular Field

Alright, let's get our hands dirty with a real problem. Theory is great, but walking through an example from start to finish is where the lightbulb really goes on. We'll use a classic scenario you are almost guaranteed to see on homework or an exam.

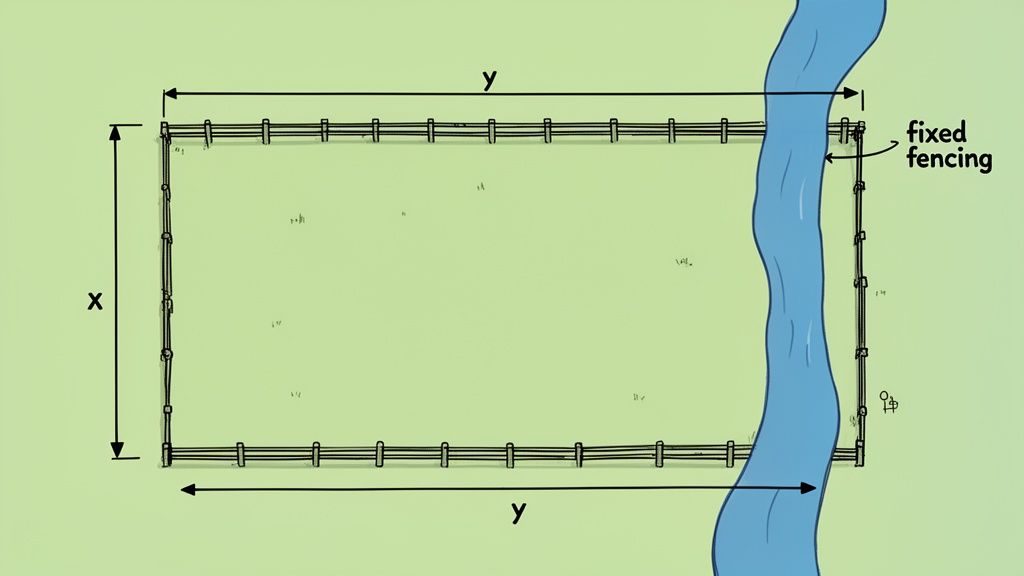

Here's the setup: A farmer has 2400 feet of fencing to build a rectangular pen along a straight river. The river acts as one side, so no fencing is needed there. What dimensions should the pen be to maximize its area?

This problem is a perfect introduction to how to solve optimization problems in calculus because it lays out the objective and the constraint so clearly.

First, Visualize the Setup

Before touching any equations, I always draw a picture. It doesn't have to be fancy. Just a rectangle with one side missing, labeled "river." Let's call the two sides perpendicular to the river x, and the side parallel to the river y.

This quick sketch immediately makes one thing obvious: the total fencing used is for three sides, not four. That's a classic detail designed to test if you're paying attention to the problem's wording.

Translate the Problem into Math

With a visual in hand, we can now build our equations. We need two things: the function we want to maximize (the objective) and the equation that limits us (the constraint).

- Objective Function (What we're maximizing): The goal is the "largest possible area." For our rectangle, that's simple: A = x * y. This is our target.

- Constraint Equation (Our limitation): The farmer only has 2400 feet of fencing. Based on our drawing, the total length of the fence is 2x + y = 2400. This is the rule we have to follow.

The problem is that our area formula, A = xy, has two variables. We can't take its derivative like this. This is where the constraint equation becomes our best friend. We can use it to get everything in terms of just one variable.

Solving the constraint for y is the easiest path: y = 2400 - 2x.

Now, we substitute this expression for y right into our area formula. This is the key move that makes the problem solvable.

A(x) = x(2400 - 2x)

A(x) = 2400x - 2x²

Boom. We now have an area function that depends only on the length x. Now we're ready for the calculus part.

Pinpoint the Critical Point

To find the value of x that gives the maximum area, we need to find the critical points of A(x). That means taking the first derivative and setting it to zero.

The derivative is:

A'(x) = 2400 - 4x

Now, set it to zero. We're looking for the spot where the function's slope is flat—our potential maximum.

0 = 2400 - 4x

4x = 2400

x = 600

So, a critical point happens when the sides perpendicular to the river are 600 feet long. But we're not done. Is this point a maximum, a minimum, or something else? We have to check.

Confirm It's a Maximum

The fastest way to verify our result is the Second Derivative Test. Just take the derivative of A'(x).

A''(x) = -4

The second derivative is a constant, -4. Since it's negative for every value of x, it’s definitely negative at our critical point.

A negative second derivative tells us the function is concave down (like a frown), which confirms that the critical point at

x = 600is a local maximum.

As a final check, let's think about the real-world limits. The length x has to be more than zero. And since 2x + y = 2400, the absolute most x could be is 1200 (leaving no fence for y). Our answer, x = 600, is safely within this practical domain of (0, 1200), giving us confidence that it's the absolute maximum.

State the Final Answer Clearly

We found the x that maximizes the area, but the question asked for the dimensions of the field. This means we need to find y as well. We just plug our optimal x back into the easiest equation we have for y:

y = 2400 - 2(600)

y = 2400 - 1200

y = 1200

So, the dimensions that give the largest possible area are 600 feet by 1200 feet. The maximum area itself would be A = 600 * 1200 = 720,000 square feet.

Worked Example: Minimizing a Box's Surface Area

Okay, to really get a feel for how these optimization problems work in calculus, you have to try them from both sides—maximizing and minimizing. Let's flip the script and tackle a classic minimization problem: designing the most efficient box.

Here's the scenario: We're building an open-top box with a square base. The catch? It needs to hold a specific volume—exactly 32,000 cubic centimeters. Our job is to figure out the dimensions that use the least amount of material. In other words, we need to minimize the surface area.

This is a great example because it uses the exact same calculus principles as a maximization problem, just with a different goal. The process is the same, but the setup requires a careful eye for the new details.

Laying Out the Problem and Equations

First thing's first: let's get a clear picture. We have a box with no top. Its base is a square, so we can call the length of a base side x. The height is a separate dimension, so let's call that h.

Now, we translate this visual into the two equations that will drive our solution: the objective function and the constraint.

- The Objective (What we're minimizing): We want to be efficient with our materials, so our goal is to minimize the surface area, which we'll call A. The total surface area is the sum of the base (

x²) and the four sides (each side isx * h). This gives us: A = x² + 4xh. - The Constraint (The rule we must follow): The box has a non-negotiable volume. The volume

Vis simplylength × width × height, orx * x * h. This has to equal 32,000 cm³. So, our constraint is: V = x²h = 32,000.

Just like before, our objective function A has two variables, x and h. Calculus requires us to work with a single variable, so we'll use the constraint equation to make that happen.

Let's rearrange the constraint to solve for h:

h = 32,000 / x²

Now we can plug this expression for h right back into our area formula.

A(x) = x² + 4x(32,000 / x²)

A(x) = x² + 128,000 / x

And there it is—our single-variable objective function, all set for us to apply some calculus.

Applying Calculus to Find the Minimum

To find the dimensions that give us the smallest possible surface area, we need to find the critical points of A(x). That means taking the first derivative and finding where it equals zero.

Before we differentiate, it's always a good idea to rewrite the function with negative exponents to make the power rule easier.

A(x) = x² + 128,000x⁻¹

Now, let's find the derivative, A'(x):

A'(x) = 2x - 128,000x⁻²

A'(x) = 2x - 128,000 / x²

Set that derivative to zero. We're looking for the point where the function's slope is flat, which is our candidate for the minimum.

0 = 2x - 128,000 / x²

A little algebra will get us to the solution for x. Let's isolate the terms.

2x = 128,000 / x²

2x³ = 128,000

x³ = 64,000

Taking the cube root of both sides gives us the value we're looking for:

x = 40

So, the side length of the square base that might give us the minimum surface area is 40 cm.

Confirming the Minimum with the Second Derivative Test

We've found a critical point, but is it actually a minimum? It could be a maximum or an inflection point. The Second Derivative Test is the quickest way to be sure. Let's find the second derivative, A''(x), starting from A'(x) = 2x - 128,000x⁻².

A''(x) = 2 - (-2) * 128,000x⁻³

A''(x) = 2 + 256,000 / x³

Now, all we have to do is plug our critical point, x = 40, into this second derivative and check the sign.

A''(40) = 2 + 256,000 / (40)³

A''(40) = 2 + 256,000 / 64,000

A''(40) = 2 + 4 = 6

The result of the second derivative is 6, which is a positive number. A positive second derivative tells us the function is concave up at that point, which confirms we've found a local minimum. Mission accomplished.

Delivering the Final Answer

The original question asked for the dimensions of the box, not just one side. We've got the base length, x = 40 cm. Now we just need to find the height, h, by going back to the relationship we derived from our constraint.

h = 32,000 / x²

h = 32,000 / (40)²

h = 32,000 / 1600

h = 20

So, the most material-efficient dimensions for this box are a 40 cm by 40 cm base and a height of 20 cm.

Pitfalls to Watch Out For (And How to Sidestep Them)

Even when you have a solid game plan for tackling optimization problems, a few common mistakes can trip you up. I’ve seen these pop up time and time again with students. The good news is, once you know what they are, they're much easier to dodge.

Forgetting to Check Your Endpoints

One of the biggest culprits is forgetting to check the endpoints of the domain. It’s easy to get laser-focused on finding where the derivative is zero, but the absolute max or min isn't always at a nice, smooth peak. Sometimes, the most extreme value is hiding right at the edge of the interval.

Think of it this way: if you're building a fence along a river, the maximum area might occur when you use all your fencing in a specific rectangular shape, but you still need to consider the "edge cases"—what if the fence is super long and skinny? Always test the boundaries of your domain.

Mixing Up the Goal and the Rule

Another classic blunder is getting your objective and constraint functions mixed up. It happens to the best of us, especially under pressure during an exam.

Here’s a simple way I learned to keep them straight:

- The objective function is your GOAL. It’s the thing you’re actually trying to maximize or minimize (e.g., Area, Profit, Volume).

- The constraint is the RULE you have to follow. It’s the limitation or fixed value holding you back (e.g., a fixed amount of fencing, a budget).

I always tell my students to literally write "GOAL:" and "RULE:" on their paper next to the respective equations. It’s a tiny habit that takes two seconds but can save you from completely derailing your solution.

Answering the Wrong Question

This one is surprisingly common. You do all the hard calculus, you find the perfect value for x, and you move on, feeling great. But wait—did the question ask for the value of x, or did it ask for the dimensions of the box, or the maximum area itself?

Make it a habit to reread the prompt one last time after you’ve found your critical points. This final check ensures you're actually providing the answer the question is looking for, not just an intermediate step. It's a simple, surefire way to lock in those final points.

We've all been there—a small mistake derails an otherwise perfect solution. Here’s a quick-reference table to help you spot and fix these common errors before they happen.

Troubleshooting Common Optimization Errors

| Common Mistake | Why It Happens | How to Avoid It |

|---|---|---|

| Endpoint Negligence | Focusing only on critical points (where f'(x) = 0) and forgetting the domain's boundaries. | Always identify your interval [a, b] first. After finding critical points, plug them and your endpoints (a and b) back into the original objective function to compare values. |

| Objective/Constraint Mix-Up | Both are equations, and it's easy to confuse which one to differentiate and which one to substitute. | Label them clearly from the start. Write "GOAL" next to the function you want to optimize and "RULE" next to the constraint equation. |

| Answering Half the Question | Stopping after finding the value of a variable (x or r) instead of using it to find the final requested quantity (like area, cost, or dimensions). | Before circling your final answer, reread the last sentence of the problem. Make sure you’ve answered exactly what was asked. |

| Derivative Errors | Simple algebra or calculus mistakes when finding the derivative, especially with complex functions (product/quotient rule). | Slow down! Write out each step of your differentiation clearly. Double-check your work before setting the derivative to zero. |

By keeping these potential pitfalls in mind, you can build a more robust and error-proof problem-solving process.

Still Have Questions About Optimization?

Even with a solid game plan, a few common hangups can trip students up when they're first tackling optimization problems. Let's walk through some of the questions I hear most often to make sure you’re ready for whatever comes your way.

Local vs. Absolute Maximum: What’s the Real Difference?

Think of a local maximum as the highest hill in a single valley. It's a peak, sure, but there might be a much taller mountain range somewhere else. The absolute maximum, however, is the single highest point across the entire landscape—the whole domain of the function, including the very edges of the map (the endpoints).

When you use the first derivative to find critical points, you're just identifying all the local hills and valleys. To find the true, absolute peak, you have a crucial extra step: you must compare the function's value at these critical points against its value at the endpoints of the domain. Whichever one is biggest, that's your absolute max.

What if the Second Derivative Test Gives Me Zero?

This is a classic "uh-oh" moment for many students, but it's not a dead end. The Second Derivative Test is a fantastic shortcut, but if it comes out as zero at a critical point, the test is simply inconclusive. It doesn't tell you anything useful—not whether it's a max, a min, or just a flat spot.

So, what do you do? You pivot back to your most reliable tool: the First Derivative Test. Just check the sign of the first derivative on both sides of that critical point. If it flips from positive to negative, you've found a local max. If it goes from negative to positive, you've got a local min.

A zero in the Second Derivative Test isn't a failure, it's just a signal to switch tactics. Always have the First Derivative Test in your back pocket; it's the one that never fails.

Can You Even Do Optimization Without Calculus?

Technically, yes, but it's usually the hard way. For very simple functions, like a basic parabola, you can find the vertex using algebra. You could also try to estimate a maximum by graphing it.

But for the complex functions you'll see in most real-world problems, calculus is hands-down the most powerful and precise tool for the job. It's what lets you find the exact optimal point with certainty, not just an estimate.

Of course, mastering the concepts is only half the battle. To really ace your exams, you also need to know how to plan an effective study schedule that helps you practice consistently and lock in what you've learned.

Feeling stuck on a tough calculus problem or need a clearer explanation for any school subject? Feen AI can help. Get instant, step-by-step solutions and chat with an AI tutor that makes learning faster and easier. Try it now at https://feen.ai.

Recent articles

Struggling with circuit homework? Learn the rules of voltage drop in a parallel circuit with simple analogies, clear formulas, and solved examples.

Learn how to write a strong argumentative essay with our guide. We cover building a thesis, using evidence, and structuring your argument for academic success.

Discover how to prepare for organic chemistry using proven strategies. Our guide breaks down the essential study methods and tools you need to succeed in Orgo.

Struggling with statistics? Learn how to solve probability problems using core concepts, proven techniques, and real-world examples in this practical guide.

Unlock the best way to study for finals with 10 evidence-based strategies. Our guide covers everything from active recall to using Feen AI for success.

Discover how to improve critical thinking skills with practical exercises, proven frameworks, and strategies for students and professionals.