Master Genetics: 8 Punnett Square Practice Problems for 2026

Struggling with genetics? Master inheritance with our detailed Punnett square practice problems, from monohybrid to sex-linked. Perfect for biology students.

Welcome to your go-to resource for mastering genetics. The Punnett square is a foundational tool in biology, but moving from theory to application can be challenging. This guide provides a curated set of Punnett square practice problems, designed to build your skills from the ground up and transform abstract concepts into concrete understanding.

We'll start with the basics, like simple monohybrid crosses, and systematically progress to more complex scenarios including dihybrid crosses, incomplete dominance, codominance, and sex-linked traits. Each problem is more than just a question; it's a mini-lesson complete with a detailed, step-by-step breakdown, strategic insights, and actionable tips to turn confusion into confidence. You'll learn how to identify parental genotypes, set up your squares correctly, and interpret the resulting phenotypic and genotypic ratios with precision.

By working through these examples, you will develop a strategic approach to genetic problem-solving. This targeted practice is essential for anyone tackling biology coursework. To delve deeper into the broader context of genetics and other biological principles, consider exploring the complete AP Biology course. Whether you're studying for an exam or just solidifying your knowledge, these practice problems will equip you with the skills to solve any genetic puzzle. We'll even show you how to use AI tools to check your work and deepen your understanding.

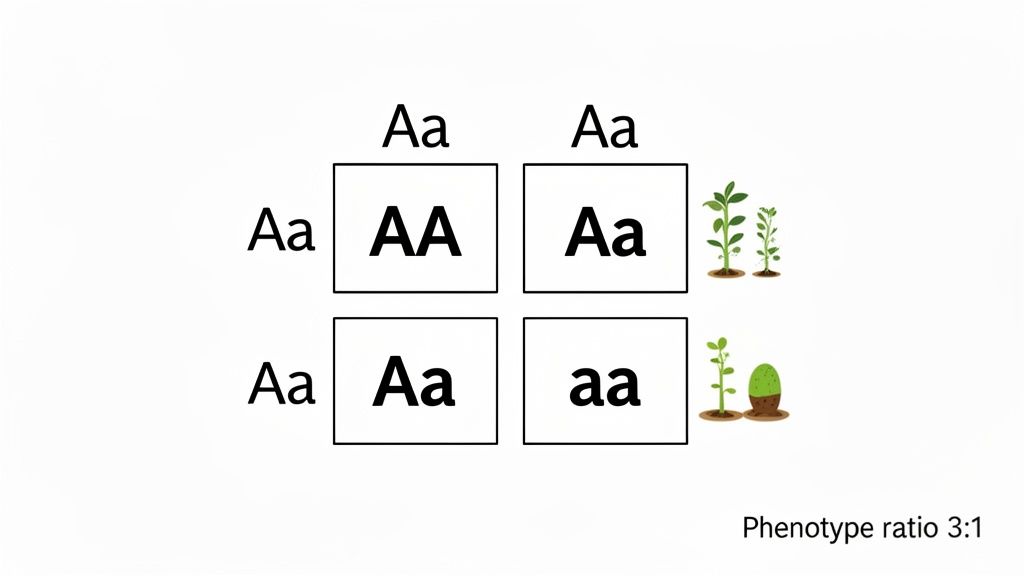

1. Monohybrid Cross

The monohybrid cross is the starting point for anyone learning genetics and is the most fundamental of all Punnett square practice problems. This type of cross examines the inheritance of a single trait, such as flower color or seed shape, determined by one gene with two different alleles. It demonstrates Gregor Mendel’s Law of Segregation, which states that an organism's two alleles for a trait separate during gamete formation, so each gamete receives only one allele.

When two heterozygous parents (e.g., Aa) are crossed, the Punnett square predicts the potential genotypes and phenotypes of their offspring. The resulting genotypic ratio is typically 1:2:1 (AA:Aa:aa), while the phenotypic ratio is 3:1 (dominant trait:recessive trait). This is because both the homozygous dominant (AA) and heterozygous (Aa) individuals will display the dominant phenotype, which is a key concept in understanding how traits are expressed. To dive deeper into the mechanisms behind this, you can explore the topic of what gene expression is and how it dictates these visible characteristics.

Strategic Tips for Monohybrid Crosses

- Define Your Alleles: Always start by assigning letters to the dominant and recessive alleles. Use a capital letter for the dominant allele (e.g., T for tall) and the corresponding lowercase letter for the recessive one (t for short).

- Set Up Correctly: Place one parent's alleles across the top of the square and the other parent's alleles down the side. This organization is crucial for accuracy.

- Analyze Both Ratios: Distinguish clearly between the genotypic ratio (the genetic makeup, like 1 AA: 2 Aa: 1 aa) and the phenotypic ratio (the physical appearance, like 3 tall: 1 short).

- Verify Your Work: For complex problems, quickly verify your ratios. You can upload an image of your completed Punnett square to an AI tool like Feen to confirm your calculations and ensure you haven't made any simple errors.

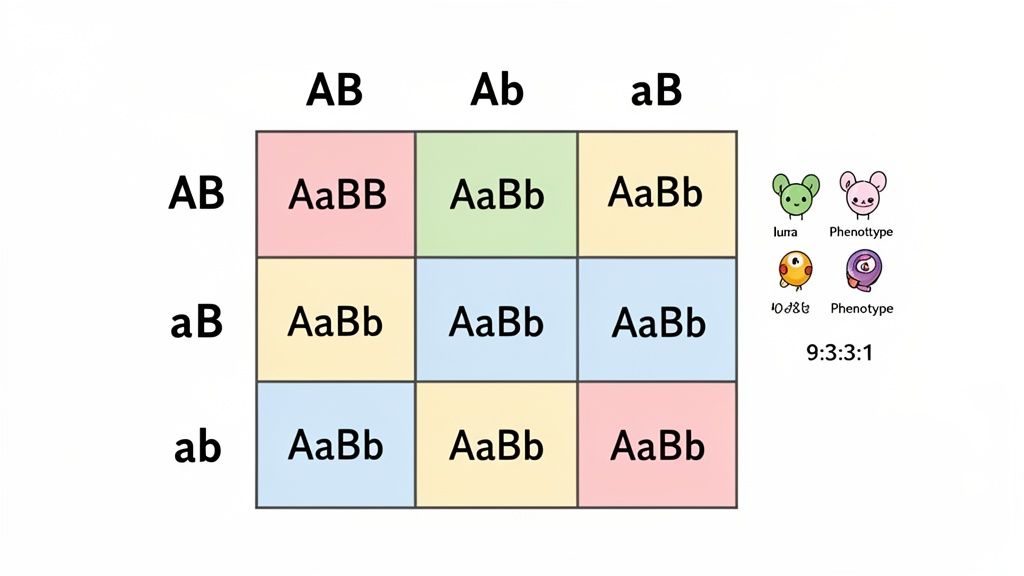

2. Dihybrid Cross

Stepping up in complexity, the dihybrid cross is an essential component of any Punnett square practice problems list. This cross involves tracking two different traits simultaneously, such as a pea plant's height and seed color. It brilliantly illustrates Gregor Mendel’s Law of Independent Assortment, which posits that the alleles for one gene segregate into gametes independently of the alleles for another gene, provided they are on different chromosomes. This requires a larger, 16-box Punnett square to account for all possible combinations.

When two parents heterozygous for both traits (e.g., RrYy) are crossed, the Punnett square predicts a classic phenotypic ratio of 9:3:3:1. This breaks down into nine offspring showing both dominant traits, three showing the first dominant and second recessive trait, three showing the first recessive and second dominant trait, and one showing both recessive traits. Understanding this ratio is a cornerstone of intermediate genetics and showcases how different traits can combine in offspring, leading to greater variation.

Strategic Tips for Dihybrid Crosses

- Determine All Gametes: Before setting up the square, list all possible gamete combinations for each parent. For a parent with genotype RrYy, the possible gametes are RY, Ry, rY, and ry. This step prevents errors in the setup.

- Use a 4x4 Grid: A dihybrid cross always requires a 4x4 grid, resulting in 16 boxes. Place the four possible gametes from one parent across the top and the four from the other parent down the side.

- Systematically Fill the Boxes: Combine the alleles from the corresponding row and column for each box. Keep letters for the same gene together (e.g., RrYy not RYry) to maintain clarity.

- Verify the 9:3:3:1 Ratio: After filling the square, carefully count the number of offspring for each phenotype. Confirm they add up to 16 and match the expected 9:3:3:1 ratio. This is a great way to check your work for mistakes.

3. Codominant Inheritance

Codominant inheritance is a fascinating pattern that offers a unique set of Punnett square practice problems where neither allele is truly dominant or recessive. Instead, when an organism is heterozygous, both alleles are fully and separately expressed in the phenotype. This results in three distinct phenotypes: one for each homozygous genotype and a third where both traits appear simultaneously, not as a blend. A classic example is the roan coat color in cattle, where a cross between a red-coated parent (RR) and a white-coated parent (WW) produces offspring (RW) that have both red and white hairs.

When two heterozygous roan cattle (RW) are crossed, the Punnett square predicts a genotypic ratio of 1:2:1 (RR:RW:WW). Unlike simple dominance, this directly translates to a 1:2:1 phenotypic ratio (1 red: 2 roan: 1 white). This one-to-one relationship between genotype and phenotype makes codominance problems a great way to solidify your understanding of how alleles can interact beyond the simple dominant-recessive model. Other examples include the human ABO blood group system, where the I^A and I^B alleles are codominant.

Strategic Tips for Codominant Crosses

- Choose Clear Notation: Since there's no lowercase recessive allele, use different capital letters or superscripts (e.g., C^R for red, C^W for white). This prevents confusion with simple dominance.

- Remember "Both," Not "Blend": The key to codominance is that both traits are expressed distinctly. A roan cow has red hairs and white hairs, not pink hairs. This is the main difference from incomplete dominance.

- Match Ratios Directly: In codominance, the genotypic ratio (e.g., 1 RR: 2 RW: 1 WW) is identical to the phenotypic ratio (1 red: 2 roan: 1 white). This is a reliable check for your work.

- Clarify Allele Interactions: If you're struggling to differentiate codominance from incomplete dominance in a word problem, use Feen AI. You can describe the parental and offspring phenotypes, and the tool can help you identify which inheritance pattern is at play.

4. Incomplete Dominance

Moving beyond simple dominant-recessive relationships, incomplete dominance introduces a fascinating twist to Punnett square practice problems. This inheritance pattern occurs when a heterozygous organism displays a phenotype that is an intermediate blend of the two homozygous phenotypes. Neither allele is completely dominant over the other, resulting in a third, distinct phenotype. A classic example is the snapdragon flower, where a cross between a red-flowered plant (RR) and a white-flowered plant (rr) produces pink-flowered offspring (Rr).

In these scenarios, the genotypic and phenotypic ratios from a heterozygous cross are identical. When two pink snapdragons (Rr) are crossed, the Punnett square predicts a 1:2:1 ratio for both genotype (RR:Rr:rr) and phenotype (red:pink:white). This one-to-one correspondence between genotype and phenotype makes incomplete dominance a key concept for understanding how genetic instructions translate directly into observable traits without one allele masking another. It challenges the simple binary outcomes of complete dominance and demonstrates a more nuanced expression of genes.

Strategic Tips for Incomplete Dominance Crosses

- Distinguish from Codominance: Remember that incomplete dominance is a blend (red + white = pink), while codominance shows both traits distinctly (a red and white speckled flower). This is a common point of confusion.

- Expect a 1:2:1 Ratio: In a cross between two heterozygous individuals, the hallmark of incomplete dominance is a 1:2:1 ratio for both genotypes and phenotypes. If you see three distinct phenotypes in this ratio, incomplete dominance is likely at play.

- Use Clear Allele Notation: To avoid confusion with complete dominance, some prefer using different letters (e.g., CR for red and CW for white). This notation can make it clearer that neither allele is recessive.

- Visualize the Blend: When solving problems, clearly define the intermediate phenotype. For example, explicitly state that Rr results in a pink phenotype to keep your analysis organized and accurate.

5. Sex-Linked Inheritance

Sex-linked inheritance introduces a unique twist to Punnett square practice problems by involving genes located on the sex chromosomes. In humans, this typically means the X chromosome. Because males (XY) have only one X chromosome while females (XX) have two, the patterns of inheritance and expression for these traits differ significantly between sexes. This concept explains why certain conditions, like red-green color blindness or hemophilia, are far more common in males.

These problems require a specific notation, using superscripts on the X and Y chromosomes to track the alleles (e.g., X^A for the dominant allele, X^a for the recessive). A male will express whatever allele is on his single X chromosome, whereas a female can be a carrier (X^A X^a) of a recessive trait without showing it. This distinction is central to solving sex-linked Punnett squares, as the probability of inheriting a trait depends directly on the offspring's sex.

Strategic Tips for Sex-Linked Inheritance

- Use Correct Notation: Always represent genotypes using the X and Y chromosomes. For example, use X^R and X^r for a color blindness gene. A carrier female would be X^R X^r, while an affected male would be X^r Y.

- Set Up Parents Accurately: Place the female's two X-linked alleles (e.g., X^R and X^r) across the top and the male's X and Y gametes (e.g., X^R and Y) down the side. This setup correctly models how sex is determined alongside the trait.

- Analyze Male and Female Offspring Separately: After filling the square, calculate the phenotypic and genotypic ratios for males and females independently. For example, you might find that 50% of male offspring are affected, while 0% of female offspring are affected.

- Track Inheritance Paths: Remember key rules: fathers pass their X chromosome only to their daughters, and their Y chromosome only to their sons. Therefore, a father cannot pass an X-linked trait to his son.

6. Multiple Alleles

Moving beyond simple two-allele systems, multiple alleles problems introduce a more realistic layer of genetic complexity. These scenarios involve genes that have more than two possible alleles within a population. Even though more than two alleles exist, any single individual can only inherit two of them, one from each parent. This concept is fundamental to understanding genetic diversity and why some traits, like human blood type, have more than two variations.

The ABO blood group system in humans is the classic example used in Punnett square practice problems for multiple alleles. This system is controlled by three alleles: I^A, I^B, and i. The I^A and I^B alleles are codominant with each other, meaning both are expressed if present, resulting in type AB blood. Both I^A and I^B are completely dominant over the recessive i allele, which codes for type O blood. This interaction creates six possible genotypes (I^A I^A, I^A i, I^B I^B, I^B i, I^A I^B, ii) and four distinct phenotypes (Type A, Type B, Type AB, and Type O).

Strategic Tips for Multiple Alleles

- Establish a Dominance Hierarchy: Before starting, clearly define the relationship between all alleles. For ABO blood types, write down: (I^A = I^B) > i. This visual guide prevents confusion.

- List Genotypes and Phenotypes: Create a small table listing all possible genotypes and their corresponding phenotypes. This serves as a quick reference when filling out and analyzing the Punnett square.

- Track Combinations Carefully: With more alleles in play, the number of potential offspring combinations increases. Be methodical when filling in the squares to ensure you don’t miss any possibilities.

- Confirm with AI: The complex dominance patterns can be tricky. You can describe the specific problem to an AI assistant like Feen, stating "Parent 1 has genotype I^A i and Parent 2 has genotype I^B i," to verify your predicted phenotypic ratios.

7. Linked Genes

Linked genes introduce a fascinating complexity to Punnett square practice problems by challenging a key Mendelian principle. These are genes located physically close to each other on the same chromosome. Because of their proximity, they do not assort independently during meiosis and are often inherited together, which violates Mendel’s Law of Independent Assortment. Classic examples include body color and wing shape in fruit flies.

This linkage results in offspring ratios that deviate significantly from the expected 9:3:3:1 dihybrid ratio. While these genes tend to travel together, the process of crossing over during meiosis can separate them, creating new combinations of alleles called recombinants. Analyzing the frequency of these recombinant offspring allows geneticists to map the distance between genes on a chromosome, a fundamental concept in genetic mapping.

Strategic Tips for Linked Genes

- Identify Parental vs. Recombinant: In a testcross, the most frequent offspring phenotypes are the parental types (non-recombinant), while the least frequent are the recombinant types. This is your first clue that genes are linked.

- Compare to Expected Ratios: If your observed results don't match the 9:3:3:1 (dihybrid cross) or 1:1:1:1 (testcross) ratios, suspect gene linkage. This deviation is a critical piece of evidence.

- Calculate Recombination Frequency: To find the map distance between two genes, add the number of recombinant offspring, divide by the total number of offspring, and multiply by 100. The result is given in map units or centimorgans.

- Use the Right Tools: For complex data, a chi-square test can statistically confirm if the deviation from the expected ratio is significant, which strengthens your hypothesis. This structured approach mirrors the rigor you'd find when following the 7 steps of the scientific method.

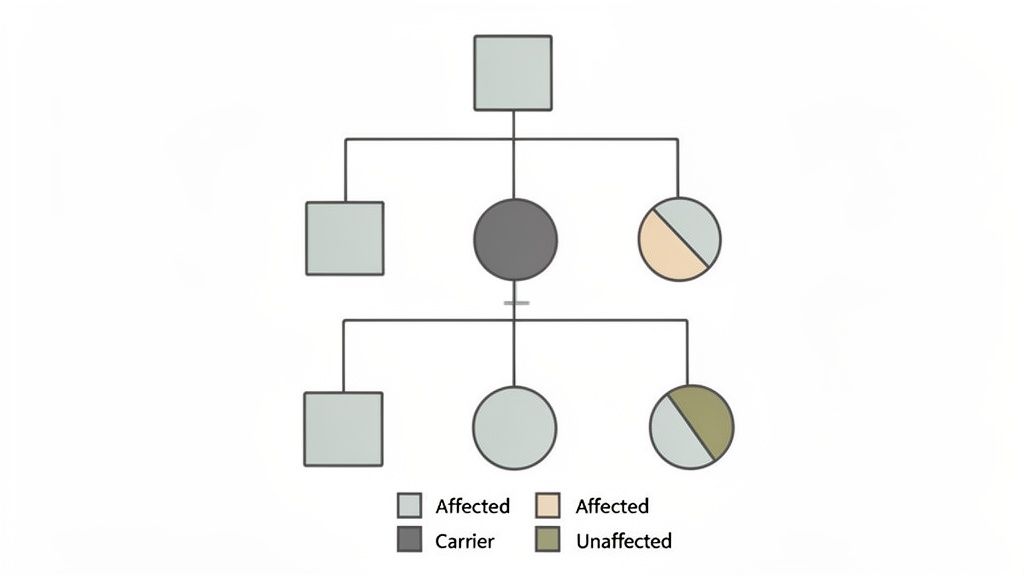

8. Pedigree Analysis

Pedigree analysis elevates Punnett square practice problems by applying genetic principles to real-world family trees. This method visually tracks the inheritance of a specific trait or genetic disorder across multiple generations. Instead of a simple cross, pedigrees use standardized symbols like squares for males, circles for females, and shaded shapes for affected individuals to map out inheritance patterns. This approach requires you to combine Punnett square logic with deductive reasoning to determine genotypes and predict future probabilities.

Analyzing a pedigree involves identifying whether a trait is dominant or recessive and autosomal or sex-linked. For example, if a trait skips a generation, it's likely recessive. If it appears more often in males, it might be sex-linked. Classic examples include tracking hemophilia in Queen Victoria's descendants or mapping Huntington's disease within a family. Documenting your findings clearly is crucial, similar to how you would structure data in a formal scientific setting; you can see examples of this in guides on the proper biology lab report format.

Strategic Tips for Pedigree Analysis

- Determine Inheritance Pattern: First, establish if the trait is dominant or recessive. A dominant trait will appear in every generation, while a recessive one can skip generations. Then, check if it is autosomal or sex-linked by looking for patterns related to gender.

- Work Backwards from Knowns: Start with individuals whose genotypes you can definitively identify. For instance, an individual expressing a recessive trait must be homozygous recessive (aa), which provides clues about their parents' genotypes.

- Assign Genotypes Systematically: Label each individual on the pedigree with their possible genotypes based on the inheritance pattern and their relationships. Use question marks for unknown alleles (e.g., A_?).

- Use Feen for Verification: Pedigrees can get complex. To ensure your deductions are sound, upload a photo of your labeled pedigree chart to an AI tool like Feen. It can help confirm your assigned genotypes and check your probability calculations for future offspring.

Punnett Square Practice: 8-Example Comparison

| Topic | Implementation complexity | Resource requirements | Expected outcomes | Ideal use cases | Key advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monohybrid Cross | Low | 2×2 Punnett square; basic allele notation (Aa) | Predictable 3:1 phenotypic (F2); 1:2:1 genotypic | Introductory Mendelian inheritance lessons | Simple, quick, clear visualization of segregation |

| Dihybrid Cross | Moderate | 4×4 Punnett square; gamete list (AB, Ab, aB, ab) | 9:3:3:1 phenotypic ratio if independent assortment holds | Intermediate genetics; AP Biology and college courses | Demonstrates independent assortment of two traits; realistic multi-trait inheritance |

| Codominant Inheritance | Moderate | Clear phenotype markers; allele notation (e.g., I^A, I^B) | Three distinct phenotypes; heterozygote expresses both alleles (1:2:1) | Blood typing, traits with observable dual expression | Distinct phenotypes with no blending; medically relevant (AB blood type) |

| Incomplete Dominance | Moderate | Controlled crosses; careful phenotype scoring for intermediates | Blended/intermediate heterozygote phenotype; 1:2:1 genotype/phenotype | Teaching blending and intermediate traits; visual demonstrations | Illustrates intermediate expression and direct genotype–phenotype match |

| Sex-Linked Inheritance | High | XY/XX notation; separate analyses for males and females | Different male/female phenotypic ratios; carrier females possible | Explaining sex-biased disorders; clinical genetics and counseling | Explains sex differences in trait prevalence; clinically important |

| Multiple Alleles | High | Dominance-hierarchy chart; expanded genotype/phenotype tables | More genotypes than phenotypes (e.g., ABO); complex dominance relationships | Population genetics, blood typing, paternity testing | Reflects real population diversity; medically and practically relevant |

| Linked Genes | High | Recombination/testcross data; map distance and chi-square calculations | Deviations from independent-assortment ratios; parental > recombinant classes | Genetic mapping, breeding studies, explaining unexpected ratios | Introduces linkage and recombination; useful for chromosome mapping |

| Pedigree Analysis | High | Family histories; standardized pedigree symbols; multi-generation data | Inheritance-pattern identification; carrier detection and risk probabilities | Genetic counseling, clinical diagnosis, forensic/paternity cases | Real-world family analysis; identifies carriers and predicts generational risk |

Your Next Steps to Genetics Mastery

You have successfully navigated a comprehensive set of Punnett square practice problems, progressing from the foundational principles of monohybrid crosses to the intricate logic of pedigree analysis. The journey through these examples illuminates a core truth of genetics: complexity is built on a foundation of simple, predictable rules. Each problem, whether exploring codominance, sex-linked traits, or linked genes, reinforces the fundamental laws of segregation and independent assortment.

The key to mastering these concepts is not just memorization, but strategic application. Before you even draw the square, your first step should always be to identify the inheritance pattern at play. This single action dictates how you assign alleles, set up the parental genotypes, and interpret the resulting ratios.

Key Strategic Takeaways

To solidify your skills, focus on these core strategies that were demonstrated throughout the article:

- Deconstruct the Problem: Break down word problems into their essential components: parental phenotypes and genotypes, the type of dominance, and the specific question being asked (e.g., phenotypic ratio vs. genotypic probability).

- Master the Vocabulary: Fluency in terms like homozygous, heterozygous, allele, dominant, and recessive is non-negotiable. Misunderstanding a single term can lead you to the wrong setup and an incorrect answer.

- Visualize the Cross: The Punnett square is your primary tool. Always label your axes clearly with the parental gametes. For dihybrid and more complex crosses, ensure you have correctly identified all possible gamete combinations using the FOIL method.

- Embrace Mistakes as Data: Every incorrect answer is an opportunity for learning. Did you misinterpret the inheritance pattern? Did you incorrectly determine the parental gametes? Analyze your errors to pinpoint weaknesses in your understanding.

Actionable Next Steps for Continued Practice

Genetics is a skill that sharpens with consistent effort. To continue building your confidence and accuracy, consider the following actions:

- Revisit and Rework: Go back to the problems in this article that you found most challenging. Try to solve them again from scratch without looking at the solution first. This active recall is one of the most effective ways to cement your knowledge.

- Seek Out New Challenges: Look for additional Punnett square practice problems in your textbook, online resources, or old exams. The more varied the scenarios you encounter, the more adaptable your problem-solving skills will become.

- Explain It to Someone Else: A powerful way to test your own understanding is to try teaching the concepts to a friend or family member. If you can clearly explain how to solve a dihybrid cross, you have truly mastered it.

For students aiming to deepen their knowledge and excel in their coursework, personalized guidance can make all the difference. To solidify your understanding of Punnett squares and tackle more complex challenges, consider working with a dedicated biology tutor.

Ultimately, mastering the Punnett square is about more than just passing your next biology exam. It’s about developing critical thinking and analytical reasoning skills that are valuable in any field. You are learning to decode the very language of life, a skill that provides a profound understanding of the natural world. Keep practicing, stay curious, and you will unlock the ability to solve any genetic puzzle thrown your way.

Stuck on a tricky homework problem? Get instant, step-by-step help with Feen AI. Simply upload a photo of your Punnett square or genetics question, and our AI will analyze your work, explain any mistakes, and guide you to the correct solution. Try Feen AI today and turn confusion into confidence.

Recent articles

Master the essential skill of converting mass to moles. Our guide provides clear examples, molar mass calculations, and common pitfalls to avoid.

Explore change in momentum, including impulse and the core formula, with clear explanations and practical examples to sharpen problem solving.

Tired of the homework battles? Learn how to motivate kids to study with practical strategies that build focus, resilience, and a genuine love for learning.

Discover how to improve test taking skills with proven strategies. Learn study techniques, anxiety management, and ways to analyze mistakes for better grades.

Discover how to overcome math anxiety with proven strategies. Build confidence with practical study habits.

Learn how to take lecture notes effectively with proven strategies. Discover methods that boost retention and turn your notes into powerful study tools.